Part 2 of 2: (Part 1 here: "Big Ben" Eastman)

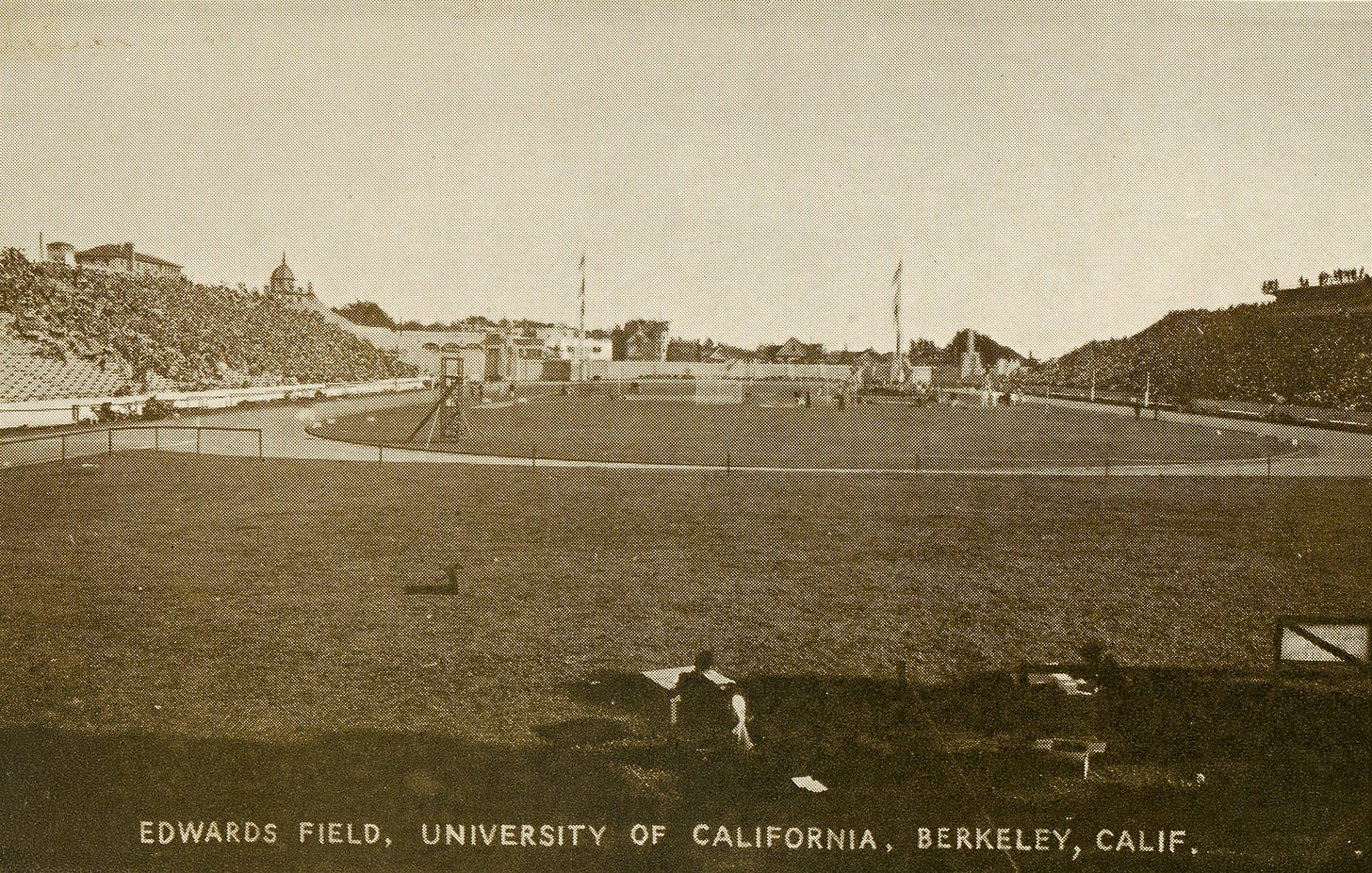

Edwards Stadium: Berkeley

It was the first of its kind; the only of its kind. A 22,000-seat, Art Deco stadium of steel and reenforced concrete, built as a track-only venue for $250,000 in 1932 ($6 million in 2025 dollars). Named after George Edwards, a long-serving math professor, athletics booster, and member of Cal’s first graduating class in 1873, a group known as the “Twelve Apostles”, the new stadium was part of a larger construction boom on campus. The skeleton of the men’s gymnasium, completed the next year and known today as Haas Pavilion, rose to the east.

Although Edwards opened its doors in early April for a Cal-USC dual meet, its grand celebration came on July 2, 1932 when 15,000 spectators packed the stands. On that Saturday afternoon it hosted, what the Oakland Post-Enquirer hyped as, the “biggest track and field meet ever held in the west”.

IC4As

The Intercollegiate Association of Amateur Athletes of America (“IC4A”) Championships was, for many years, the pinnacle of collegiate track and field. Held annually since 1876, first in New York and then alternating between Harvard and the University of Pennsylvania for three decades, the meet predated the first NCAA Championship by almost half a century. Staging the IC4As at Berkeley would prove to be an historical aberration.

Two hundred and twenty eight athletes from 36 eastern colleges and universities competed. Cal Berkeley, Stanford, newcomer UCLA, and defending champions USC represented California. Over the prior decade, Cal, Stanford and USC had each won three championships to just one for an eastern school. The west dominated the early years of the NCAAs as well.

Based on this run of success, it seemed only fair to have a west coast host for once. But the choice had more to do with scheduling and the demands of transcontinental travel than any track results. With the Olympic Trials set for Palo Alto in mid-July and the Olympics in Los Angeles at the end of the month, it would have been impractical to expect Olympic hopefuls to make two week-long train journeys so close to the Games. Berkeley was the beneficiary.

Dink vs. Robbie

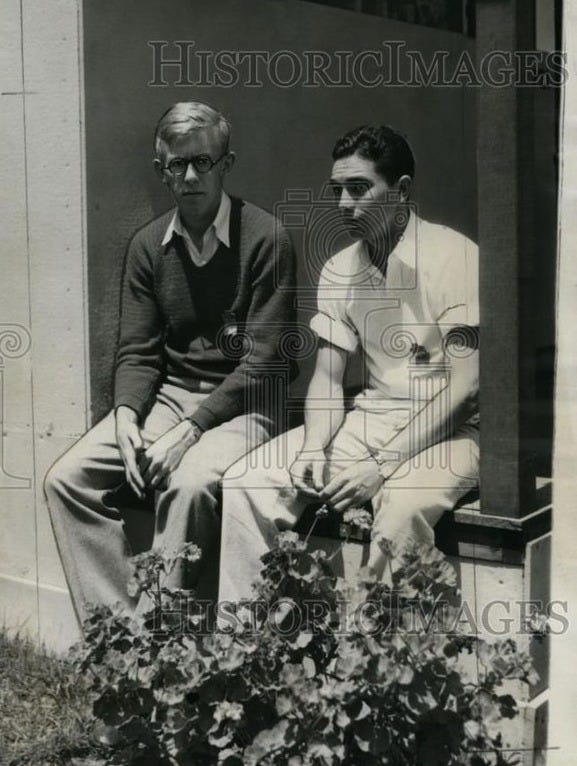

After several months in the hospital with “acute arthritis”, 35-year-old Stanford coach “Dink” Templeton had taken to calling himself “Old Crip”. But he was out now, patrolling the infield and complaining to newsmen of the disrespect shown by the “Eastern Elite.” He accused east coast coaches of being “doubting Thomases” who frequently questioned the times reported of west coast stars, his own record-breaking Ben Eastman among them.

When eastern coaches acknowledged California’s championship dominance, they attributed the success to year-around training in a favorable climate. They also claimed that the top three west coast programs hoovered up all the best regional athletes, while eastern institutions had to compete for every athletic recruit.

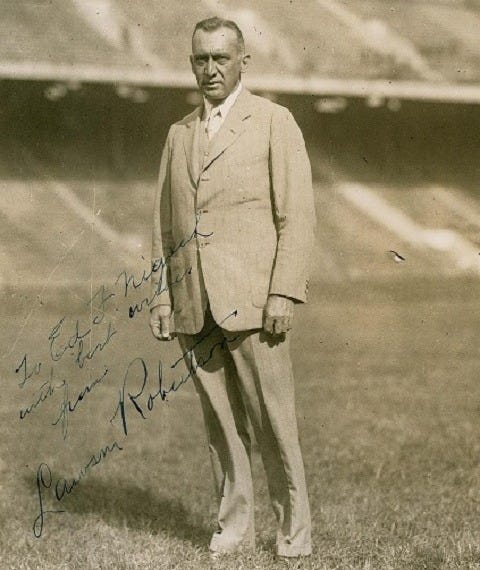

There was an east vs. west coaching rivalry to be sure. The University of Pennsylvania’s Lawson “Robbie” Robertson, who once ran a three-legged world record with Dartmouth coach Harry Hillman, would soon be coaching the United States track & field team for a third consecutive Olympics. He had named six assistants, including Hillman and Oregon’s Bill Hayward, but Dink was not among them despite the two national championships on his coaching resume.

Eastman vs. Carr

University of Pennsylvania junior Bill Carr had been a high school sprint and long jump champion, first in his Pine Bluff, Arkansas hometown, then as a senior at Mercersburg Academy in Pennsylvania. At Penn he was a popular student, serving as president of his sophomore class and winning the prestigious “Spoon” his senior year. He arrived at the IC4As with a national indoor 300-yard crown to this credit and a modest 48.2-second best in the 440-yards, run in an April intra-squad meet to select the team’s mile relay.

Although an accomplished sprinter who’d reportedly broken “even time” (10 seconds) in the 100-yard dash, he didn’t seem to pose much of a challenge to Stanford’s Eastman who’d run nearly two seconds faster in the quarter on multiple occasions. Although Carr’s effortless-looking win in qualifying served notice that he was ready to run faster, even his own coach told reporters that Eastman would “probably win.” Where Dink was talking of records to come, Lawson was all too happy to let another athlete feel the pressure.

Eastman and Carr were both college juniors studying economics, both had older brothers and both initially started as jumpers (Carr once high jumped six feet). But that’s where the similarities ended. Newsmen branded the contest as “Big Ben” (6’1”) vs. “Wee Willie” (5’6”), the middle-distance man vs. the pure sprinter, the blond vs. the brunette, the gangly loper vs. the smooth muscular athlete.

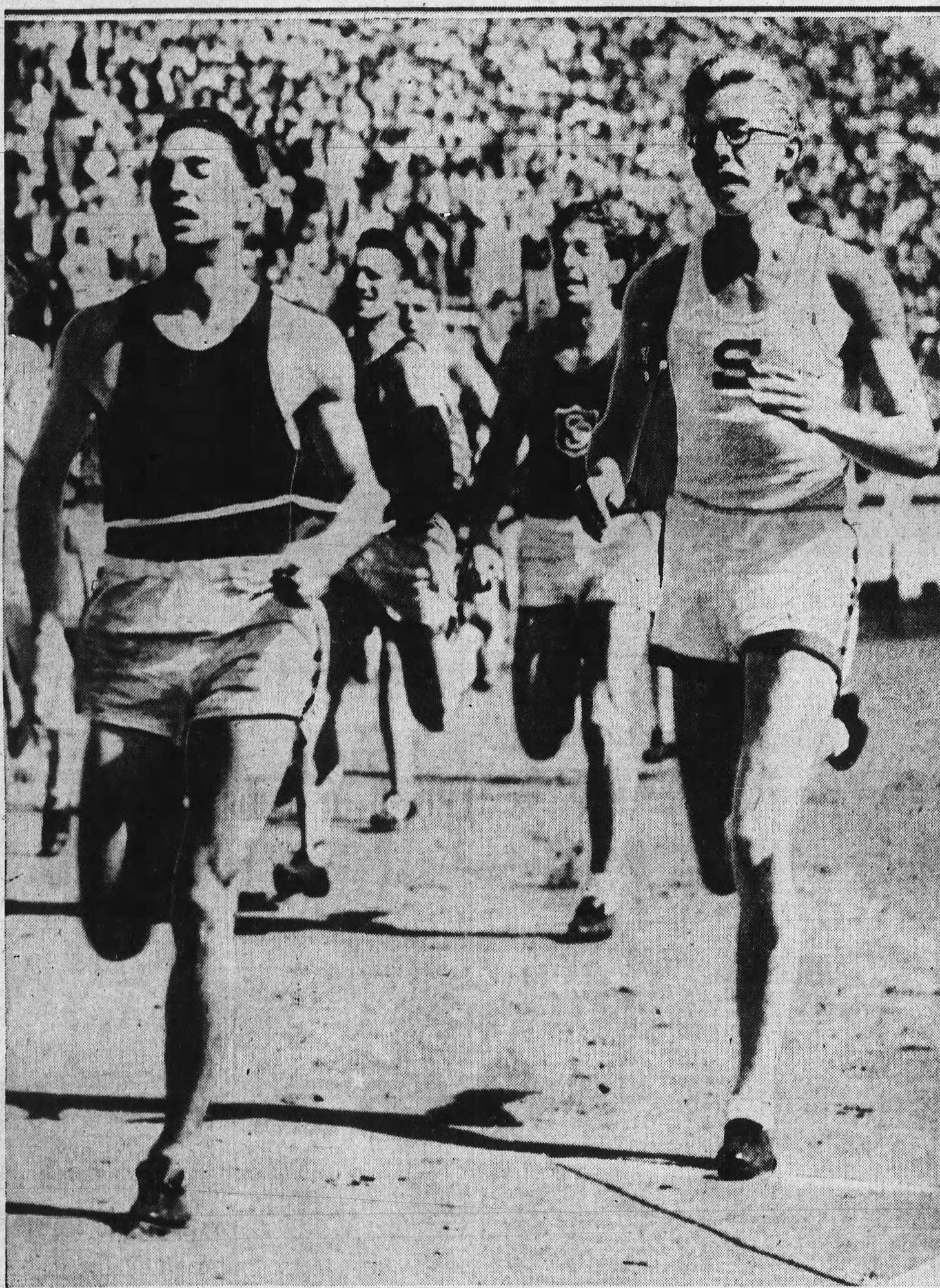

Shortly before 3:30 in the afternoon in near-perfect East Bay conditions, six athletes took their marks at the far end of the 220-yard straightaway where tennis courts sit today. Eastman had pole position, and despite his usual slow start, he led into the turn as he so often had. Carr started on the far outside, but pulled even as they hit the homestretch and seemed to ease away from a tired-looking Eastman over the final 50 meters. In was an entirely unfamiliar experience for the Stanford man.

Meet officials, matching in their white trousers, blue jackets, and red-ribboned straw hats were as aghast as the crowd. Head official Gus Kirby was testing his new fully-automatic timing system which recorded Carr at 46.99 seconds, two-tenths of a second ahead of the world-record holder. The Oakland Tribune found it utterly shocking: “Can it be? Oh, shades of Caesar, an idol has gone kerplunk. Ben Eastman takes a licking!”

Eastman doubled back an hour later in the half-mile and won unchallenged in a new IC4A record. But he didn’t look himself. A year earlier he’d claimed: “There’s no such thing as a burnt-out athlete.” But had the fair California weather proved to be a curse, encouraging him to chase records in March and demanding that he stay sharp over five months of racing?

Dink didn’t think so. And he was fuming at the defeat to one of Lawson’s boys. His months-long confinement to a hospital bed couldn’t have helped his state of mind.

Stanford Stadium: Olympic Trials

Two weeks after his defeat and two weeks before the Los Angeles Olympics, Eastman was back on his home track. Before IC4As, Robertson had suggested that, based on his sensational form, Eastman might be granted a spot to represent team USA in the 400 meters without needing to run the event in the Olympic Trials (allowing him to just qualify in the 800 meters). US Olympic officials, led by Avery Brundage, would have none of it. It was the right decision as it would have set a terrible precedent in the country’s top-three selection process. That didn’t stop some west coast commentators from claiming Ben was being treated unfairly because the Eastern Elite disliked his coach.

Facing the prospect of needing to run four races in two days, Dink and Ben had a decision to make. Run both and risk running something less than your best, or pick one and show off your record-breaking form? Dink opted to focus on the 400 meters, believing that, despite his defeat at IC4As, Eastman was still the better runner. Surely, skipping the half-mile would return the pop to his star’s legs. And Dink, if not the humble Eastman, was desperate to prove that Stanford outclassed Penn.

But the Trials were a carbon copy of the IC4As. Eastman led by 3 yards half-way home and Carr swept home to victory from the outside position in a nearly identical clocking. Eastman would have won the 800 meters comfortably and been a gold medal contender. But the world will never know.

Los Angeles Coliseum: 1932 Olympic Final

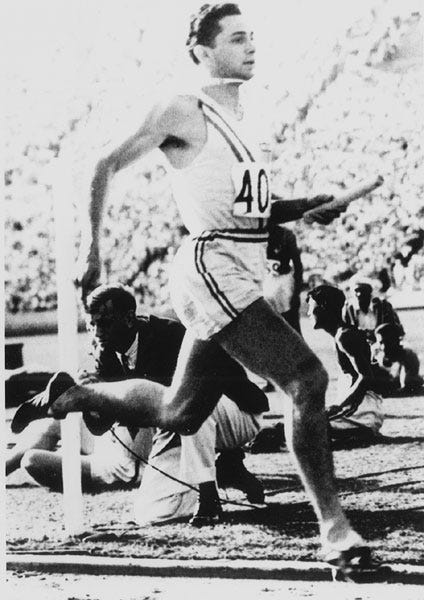

On August 5th, a day after running two preliminary heats and just two hours after the semi-final, six finalists took to their lanes for the Olympic 400-meter final. But it was always going to be a two-man race. The New York Times called it the “400-meter race of the century” even though Carr had beaten Eastman in both meetings and had run faster in each of the three qualifying rounds. Did Eastman have another gear he wasn’t showing?

Perhaps the format would favor Eastman. Unlike the one-turn, un-laned quarter-miles run in the US, the international track federation required that Olympic 400-meter races be held around the entire oval in lanes (beginning in 1962 records set on panhandle tracks were no longer allowed and 440-yard tracks were phased out). With Eastman in lane two and Carr in four, the Stanford man had his rival in his sights and got out quickest, making up part of the stagger in the first 200 meters. But Carr clawed most of it back around the final curve and caught Eastman on the straight, pulling away decisively over the final 50 meters in a world record 46.28 seconds. Once again, Eastman was two-tenths of a second back. Although fighting a sinus infection, he made no excuses, acknowledging that “Bill’s just too fast for me. You don’t need to sympathize. I know when I’m licked by a better runner.”

Even the still-unwell Dink finally accepted that Carr was the faster man. But when asked if the “feud was over”, the fiery coach, despite being stretchered to and from the Olympics, shot back “Hell no! Wait until next year.”

Two days later the American 4x400-meter relay team won gold in a new world record. Carr had earned the anchor leg but collegians from Indiana, USC and Yale ran the first three legs. Why had Robertson not put Eastman on the team? Surely, he was better than the men who had finished 4th, 5th and 7th in the Trials, even if he was a bit fatigued. Had his coach’s abrasive personality cost him? It wouldn’t be the last time relay controversy followed Robertson. In the Berlin Olympics, the Penn coach kept two Jewish athletes off the 4x100-meter relay so as to not offend Hitler.

Postscript

Eastman graduated Stanford in 1933 but stuck around to earn his MBA. Running for the oldest athletic club in the US, the San Francisco-based Olympic Club, he set a new world record for the half-mile (1:49.8) at Princeton in June 1934 and hung up his spikes. He came out of retirement to make a run at the 1936 Olympic team but came up short at the Trials.

He had been the rare 400/800 star. Many have excelled at the 200/400 double and the 800/1500 double, but concurrent world records at events that straddle the sprint/endurance line have been scarce. UPenn star Ted Meredith and Cuban Alberto “El Caballo” Juantorena, who won both events in the 1976 Olympics, are the only others to have set 400 and 800 meter world records in their track careers.

Bill Carr never lost a collegiate 400-meter race but his running career ended abruptly on Friday evening March 17, 1933. Out for a ride with a friend and two young women, Carr was standing on the car’s running board when they hit another vehicle. Thrown to the ground, he suffered multiple fractures in both ankles and broke his pelvis. He had intended to retire after the 1933 season since he “couldn’t be an athlete and a businessman” but a post-Olympic season might have produced even faster marks. His 46.28-second gold-medal run remained the 400-meter school record at the University of Pennsylvania for 93 years.

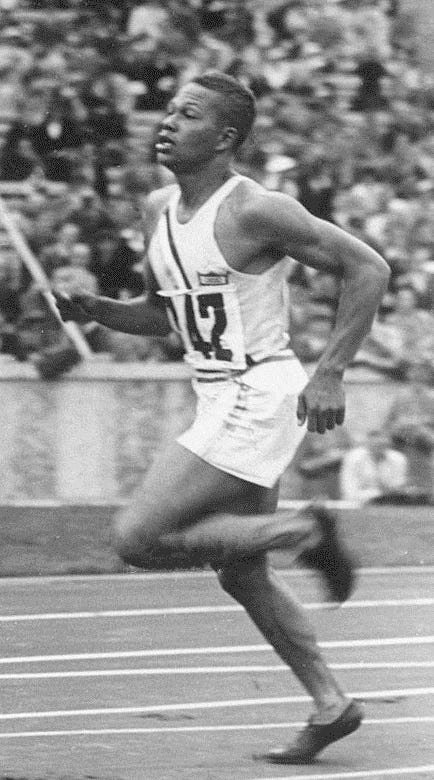

In 1932 Ben Eastman and Bill Carr were the fastest quarter-milers in the world. Only when Oakland-born Cal star Archie Williams ran faster in 1936 were the pair dethroned.

This is a great story. The East Coast - West Coast rivalry reminds me of “Seabiscuit” / Santa Anita

What is “the Spoon?”

Great account, Josh. I had no idea the IC4A’s came west to Edwards in ‘32, and that Carr beat Eastman there as well. You bring these times alive.