The First Olympic Photo Finish

"When I was in high school, Eddie and Ralph were my idols." - Jesse Owens

No one in the Coliseum knew for certain who’d won the men’s 100-meter final. Foreign dignitaries in silk toppers, Angelenos sweating in straw boater hats and finely dressed ladies under parasols, all were left wondering. Everyone in the Olympic record crowd of 65,000 had witnessed the same scene: two Americans with red, white and blue USA stripes across their chests and kangaroo leather A.G. Spalding spikes on their feet breaking the tape as one.

In the Tunnel of Doubt

Moments earlier, six of the world’s fastest young men—three Americans and sprinters from Germany, South Africa and Japan—paced in the shadows of the grand stadium’s west-end tunnel. Anxiety, thick as smoke, hung in the air. They were, as defending champion Percy Williams once put it, “scared as blazes.”

It was a hot, dry August afternoon with temperatures in the eighties and a slight sea breeze under azure skies—the perfect kind of day to shatter sprint records. The cinder track was considered the fastest in the world. Plowed, watered, and rolled smooth with an “almost satin texture” according to British 800-meter champion Tommy Hampson, it was “like running on a springboard” reported a New York Daily News sports columnist.

Trowels in hand, the finalists, all Olympic novices, dug their two starting holes in the cinders—the rear firm and flat for their lead leg, the front a foot behind the start line and sloping gently upward to prevent stumbles from their power leg. American George Simpson had recently bettered the 100-yard dash world record using mechanical starting blocks, but the record would go unratified. And on this day, he would have no such device. Deemed too controversial as an “artificial aid”, the blocks would not be allowed in Olympic competition until 1948.

If you’re enjoying my posts, please share on social media, e-mail or however you are comfortable. Thank you!

Sweatsuits shed and tense muscles shaken out a final time, the sprinters folded into their crouch positions. Over the loudspeakers the public address announcer asked for silence. Behind the runners, the portly Bavarian starter Franz Miller, wearing a white knee-length coat resembling a butcher’s jacket, brought the runners to their marks and set them in his native German tongue: Auf die Plätze and fértig!

The field rose as one, their weight balanced precariously on thumbs, fingertips and toes. Leaning their bodies forward, they raised their hips slightly above their shoulders now parallel with the freshly-chalked starting line. Chests heaved in anticipation, but a fraction of a second before Miller could fire his gun, the South African sprang off the line. Perhaps his nerves were frayed in the pre-race tension. More likely, as one of the field’s underdogs, he hoped to gain the slightest of advantages by anticipating the gun. Whatever the reason, the judges caught the infraction, and the runners were recalled to the starting line by a second shot from the pistol. They prepared for release down their four-foot corridors once more.

Finally, they were away. From the crowd’s perspective, smoke billowed overhead and the racing began seemingly a fraction of a second before a gunshot cracked the silence. Running in the inside lane wearing the Hinomaru (“circle of the sun”) on his chest and a white hachimaki headband, Takayoshi Yoshioka, with the fastest reaction time and most explosive start, grabbed an early lead. But by forty meters, Eddie Tolan had taken control of the race nearest to the stands. His stride was just six-feet, but his spikes chewed up the cinders faster than any man alive.

Inseparable Pals

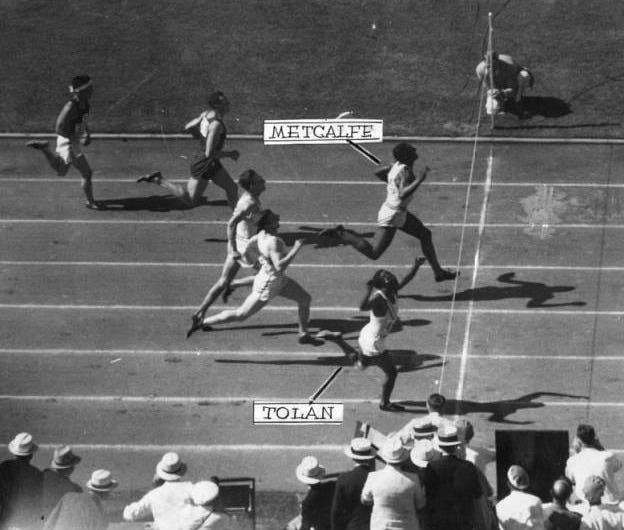

Only one man, Tolan’s teammate Ralph Metcalfe, could catch him. Metcalfe took longer to reach his top speed as the tallest sprinter in the field, but once he got going, he was the world’s fastest closer. Jesse Owens himself claimed that Metcalfe had “the greatest finish of any runner who ever lived”. Head bobbing and arms pumping furiously from the center of the track, Metcalfe pulled even with Tolan at eighty meters.

Embarrassingly shut out of the 100-meter medals four years earlier, American coaches hoped to see the Stars and Stripes rise above the grand stadium’s white colonnaded peristyle after the race. Tolan and Metcalfe gave them the best chance. They trod similar ground: NCAA track champions (Michigan and Marquette) from the Midwest (Detroit and Chicago); members of the same Greek fraternity (Alpha Phi Alpha); and Olympic Village roommates. They also shared the ever-present experience of racial prejudice in their overwhelmingly white institutions. The Pittsburgh Courier called them “inseparable pals”, but as rivals, the truth was more complicated. According to teammate Hector Dyer, Metcalfe thought Tolan was a “nice fellow” who also drove him crazy: “All the time he’s rattling me.”

At just 5’4” and 140 pounds, Tolan had a short and stocky build—“chunky” according to Team USA’s Official Olympic Report, “squat” and “dumpy” to harsh journalists. He wore a bandage on his left knee from an old football injury and horn-rimmed glasses taped to his temples. Looking more professor than athlete, with a prematurely receding hairline, he chewed gum behind a gap-toothed smile to calm his nerves as he ran.

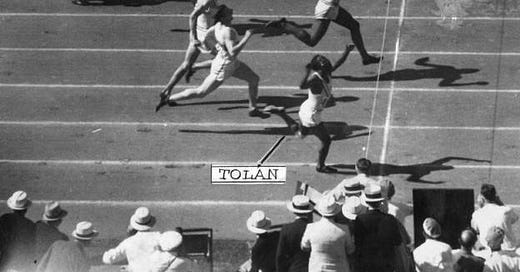

The “brawny” 5’11”, 180-pound Metcalfe and his pomaded hair towered nearly a full head over his rival. Every muscle and vein bulged from his chiseled frame—”Apollo” to fawning scribes. He appeared physically superior in every way imaginable. Yet to the naked eye, nothing separated the two at the finish line. Metcalfe’s momentum swept him to and through the line and he galloped a few yards beyond in anticipation of being declared the winner. Tolan seemed to agree and congratulated him on his win as the two embraced.

A Gnat’s Eyelash

But not even the six finish line judges with the best view were sure of the result. Years of preparation, ten seconds of racing, and now several tension-filled minutes. Using a new “two-eye” camera patented at Bell Labs by one-time Columbia University sprinter and long-time track coach and US Olympic official, Gustavus Kirby, the judges analyzed film of the finish. One image captured the finish line from a 15-foot-tall tower. The other recorded time from a clock controlled by a tuning fork and started automatically with the firing of the gun. Frame by frame, reviewing all 128 stills per second, the judges did their best to declare a winner and to record his time to a hundredth of a second. It was an impossible degree of accuracy using older hand-timing which had been rife with human error, incompetence and corruption. As groundbreaking as fully automatic timing was, as with starting blocks, it would not be used officially in the Olympics until 1960.

Tolan came through straight as a ramrod with his head flung back and his arms raised high over his head. Metcalfe’s chest appeared to reach the twine that marked the finish line a millisecond before the same tape bulged from Tolan’s lane. And without question Metcalfe’s foot crossed first and his entire body swept past the finish before Tolan—both of which were irrelevant in determining a winner as were one’s head, arms, and legs.

Whose entire torso had crossed first? Unlike today when any part of the torso—defined as shoulders to waist—reaching the nearer edge of the line counts as finishing, in the 1932 Olympics IAAF rules stated that a runner’s entire torso had to cross the line before stopping the clock.

After thirty minutes, a mighty roar rose from the crowd as the Coliseum announcer at last shared the result of the first photo finish in Olympic history. By a mere two inches, or five thousandths of a second, Eddie Tolan was declared the winner in 10.38 seconds. They were separated by no more than “a gnat’s eyelash” according to legendary sportswriter Grantland Rice. The full torso rule would be changed later in the year, but too late to help Metcalfe. For the first time, a black man would be crowned sprint champion. Just not the man most expected. Two days later Tolan would top Metcalfe in the 200 meters, again under controversial circumstances (but that’s another story that deserves its own account).

To the day he died, Metcalfe was never convinced that he’d lost the race. But he never protested. Instead, he chose to follow the “fine tradition of Olympic sport—to lose with a smile and sincere congratulations for the winner.” “Losing”, he reflected, “made me a bigger person.”

World’s Fastest Man

With Tolan’s retirement after the 1932 Olympics, Metcalfe’s undisputed reign as world’s fastest man stretched over three years. In his autobiography, Jesse Owens wrote that Metcalfe was “the greatest sprinter of his day… the best. Me included.” The Buckeye Bullet wasn’t just being kind. In 1933, 1934 and 1935 Metcalfe beat Owens in the AAU Championships. He beat everyone in every race he contested from 40 yards to 200 meters. Not until 1936 would Jesse establish his superiority. Metcalfe’s long-sought gold medal came, at last, in the 1936 Berlin Olympic men’s 4x100-meter relay when he took the baton from, who else, Jesse Owens.

Black History Month

But Ralph Metcalfe was so much more than a one-time fastest man alive. In 1970, after decades in Chicago politics representing his Bronzeville neighborhood, he was elected to the US House of Representatives from Illinois’s 1st congressional district. His win extended an unbroken chain of African-American representation from the district stretching back to 1929 when Oscar Stanton De Priest became the first black man elected to Congress in the post-Reconstruction era.

Metcalfe was a founding member of the Congressional Black Caucus in 1971, introduced a joint resolution in the House designating February as Black History Month in 1976, championed civil rights legislation, challenged redlining, and parted ways with Mayor Richard Daley’s political machine over unaddressed police brutality.

But perhaps his most consequential, and fitting, legacy was in co-sponsoring the Amateur Sports Act of 1978. Signed into law less than a month after his death, it drew on his athletic experience, provided federal funding for American Olympic athletes and increased opportunities for minorities, women, and disabled athletes to participate in amateur sports. It also created legal protections for athletes such as due process and the right to appeal eligibility disputes. Having seen his one-time rival and friend Jesse Owens fall victim to the whims of the AAU’s decision makers mere days after his historic performances in Berlin, Metcalfe recognized the extreme power imbalance between athletes and the sport’s governing bodies who controlled them. As Metcalfe put it, “I used to be called the world’s fastest human—I have never run from a fight.”

Thanks for rescuing these fascinating Olympic stories from the dustbins of history!

Fabulous article. Puts you right at the finish line of the closest race in history.

Love this stuff.