Hurdling from a T to an L

How a Dartmouth College track coach & professor made the sport safer

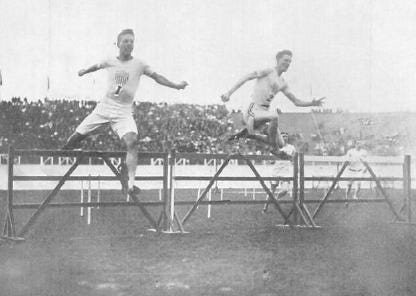

The Irishman couldn’t believe his luck. His nearest competitors trailed by a full stride as he neared the tenth and final hurdle. Robert Tisdall had been a champion high hurdler and an all-around great athlete at Cambridge University. But on the afternoon of August 1, 1932 he was racing the 400-meter hurdles for only the fifth time in his life. The six-man field, quite possibly the most loaded in hurdling history, included two past and two future Olympic champions in the event. Watching Tisdall approach the final barrier, one incredulous film announcer asked “who the hell is this?”

It was a fair question. Reigning champion, British flag bearer and Member of Parliament David Cecil, better known as Lord Burghley, was already a track legend. In his final year at Cambridge in 1927 he became the first man to run the perimeter of the Great Court at Trinity College before the clock finished striking twelve. In the 1981 Oscar-winning film Chariots of Fire, sprinter Harold Abrahams, who never attempted the feat, is credited with being first. Because of the snub, Burghley, later President of the IAAF and Vice President of the IOC, refused to let his name be used in the movie.

The Burghley-inspired film character, Lord Andrew Lindsay, set full champagne glasses on each of the thick crossbars to practice not hitting the hurdles. The real Burghley used matchboxes which he purposely tried to knock off with his lead leg. As his daughter Lady Victoria Leatham later quipped, “He was never one to waste champagne.” The evening after his history-making Great Court run one can imagine that a bottle or two were uncorked in his honor.

Tisdall and the T-Shaped Hurdle

Track athletes and fans have long debated—what is the hardest race? As a former 800-meter runner I can appreciate the case for the two-lapper. My 400-meter-racing daughter would argue that the long sprint is toughest. But nothing can be more difficult than the 400-meter hurdles. As in the flat 400 meters, lactic acid fills the sprinter’s legs in the homestretch, with the added difficulty of hurdling 36” (30” for women) barriers just as full-body fatigue sets in. It’s a recipe for disaster.

Robert Tisdall could attest to this, once commenting that hurdling presented an “ever-present risk of coming a cropper at any moment.” Telling himself to take no risks, he stutter-stepped and leapt the final hurdle “clear and high”. Or so he thought.

But just 40 meters from the finish he clipped the inverted T-shaped barrier with his left heel. He stumbled ever so slightly on legs that felt like “bags of skin filled with sand.” His head began to tilt back. Surely memories of falling at the last hurdle while leading a race versus Princeton and Cornell on New York’s Travers Island flashed through his mind. He’d lost that race three years before, but the round cinder scar on his knee would last a lifetime.

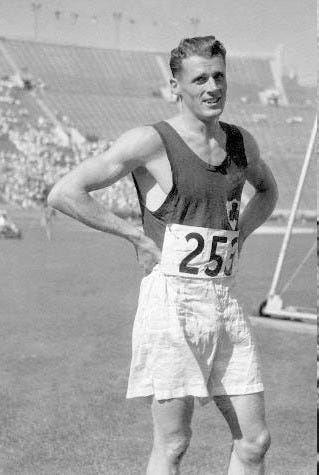

In the Memorial Coliseum stands, U.S. Assistant track coach and hurdle specialist Harry Hillman focused on the two Americans gaining ground on the Irishman. Morgan Taylor, the 1924 champion and US flag bearer, had briefly attended Dartmouth College to hone his craft under Hillman. Taylor was closing on Tisdall, but it was the 6’3”, rail-thin LSU star Glenn “Slats” Hardin who was storming home from the outside lane. (Hillman also took interest in Lord Burghley who had sought him out for advice and later became a friend).

But as an ex-hurdler himself, Hillman was also concerned with athlete safety. Hurdles had changed little in the preceding half-century. When hit they often careened upward and caused many nasty falls on rough cinder tracks. Hillman had seen too many seasons and dreams cut short through injury. His own champion hurdler, Monty Wells ‘28, once clipped a hurdle and was out for six months, missing his chance at an Olympic berth.

To mitigate the risk, Hillman had been working on a better design for three years, but the barriers used in Los Angeles that afternoon would have been familiar to spectators at a nineteenth century Oxford-Cambridge meet. As with fully-automatic timing and starting blocks, the track powers-that-be were slow to adopt new innovations.

Despite the stumble, Tisdall held on for the win in 51.8 seconds. He won gold—only the second in independent Ireland’s history—but was denied the world record because rules of the day nullified marks if an athlete hit any of the hurdles. Future Berlin gold medalist Glenn Hardin, in a procedural oddity, finished second but was credited with a new world record. (It would be the last 400-meter-hurdle race the LSU star would ever lose). That rule, like the antiquated hurdle design, would soon be a relic.

Harry Hillman

A Brooklyn native, Hillman served in New York’s National Guard and represented the New York Athletic Club in the 1904 St. Louis Olympics where he won three golds including the 200- and 400-meter hurdles. Four years later he won silver in London, cementing his place as one of the era’s best hurdlers.

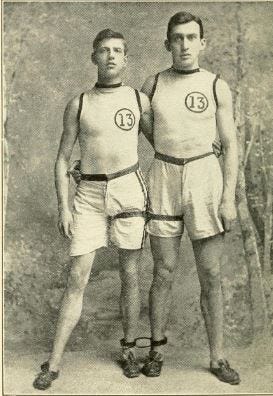

Before he began his 35-year-run as Dartmouth track coach, Hillman had one more record to set. With his friend, one-time NYAC teammate, and future University of Pennsylvania and 1932 American Olympic head track coach Lawson “Robbie” Robertson, Hillman established a world record that is unlikely to be challenged. Running in the annual Military Athletic League meet at the Thirteenth Regiment Armory in April 1909, the pair ran 11 seconds flat for the 100-yard three-legged race.

Moving on to more serious endeavors, Hillman was soon preparing his athletes for the 1912 Stockholm Olympics. All-around star Harry Worthington ‘17 competed in the long jump while Marc Wright ‘13 took silver in the pole vault, having earlier become the first man to clear 4 meters.

But it was in the hurdle events that Hillman excelled as an athlete and coach. Perhaps his best-known athlete hailed from southern California by way of Saskatchewan. After transferring from USC, Earl “Tommy” Thomson ‘22 set a world record and won gold for Canada in the 1920 Olympic 110-meter-high hurdles. After a brief stint as Hillman’s assistant, Thomson began a long coaching career at the United States Naval Academy.

In July 1930 Hillman, Thomson, and his ex-rival and then Georgia Tech coach Harold Barron introduced a new hurdle designed to reduce dangerous falls. As Hillman explained it, the old upright sat in the center of the base which, if hit, caused the hurdle to rise up two inches, often catching the hurdler’s trail leg. His new design moved the upright to one-third the distance from the front of the base, effectively eliminating the dangerous rise. It was well-received. Both the Association of Track Coaches of America and the IAAF accepted it as the new gold standard. The Associated Press reported that it would “undoubtedly be used in future Olympic competition.”

In February of 1931, in collaboration with Professor Emeritus Frank Austin of Dartmouth’s Thayer School of Engineering, Hillman filed U.S. patent # 1907149. Austin was the perfect partner. Soon after graduating from the College in 1895 he served as a physics assistant where he recorded the first clinical X-rays in the United States with his own equipment. He retired early from teaching but was always tinkering and inventing in his “Austin Workshop” on South Park Street. In 1931 he found commercial success patenting and building ant farms which became widely popular for several years. By comparison, improvements to the hurdle were small fry.

The patent filing noted several key features: a weighted, rounded base for easier rocking and a crossbar that could be easily deflected, would not rise if hit and would automatically return to its normal position if disturbed. Given rules of the day, they also developed a mechanism involving a pendulum and a spring-pressed pin set in the rounded base to record any movement of the barrier.

This final innovation proved unnecessary with the new hurdle’s adoption. The weighted barriers fell forward, dramatically lessening the chance of injury as intended, but they also slowed the hurdler down if hit. No longer would athletes be disqualified or lose out on a record for hitting too many barriers. The hurdle had changed and so had the rules.

The Hillman/Austin patent was accepted in 1933, and through continuous improvement the lighter, more forgiving L-shaped hurdle that track athletes know today made its debut in 1935. Austin moved to Florida in the 1940s while Hillman continued to be the “best dressed” man in Hanover until the day he died at Dick’s House in 1945.

The next time you see a hurdle race, be it the incomparable Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone chasing the 50-second barrier or the chest-slapping Norwegian Karsten Warholm, remember, we have a Dartmouth coach to thank for those L-shaped barriers.

2nd place gets the world record, crazy! Love the insight on the evolution of the hurdle!

I really enjoyed the article. The combination of sports and history is great reading.