Two years ago today, Kenya’s Faith Kipyegon ran one of the most memorable mile races in history. That warm evening in Monaco she ran away from the best in the world to shatter the women’s mile world record by nearly 5 seconds, stopping the clock at 4:07.64. Her 1500-meter world record of 3:48.68 set at the Prefontaine Classic earlier this month suggests she can run even (slightly) faster. She is arguably the greatest female middle-distance runner of all-time and is the only three-time Olympic gold medalist in the 1500-meters. For all of this, she should be celebrated.

Which is why I found last month’s cringe-worthy, Nike hype-fest dubbed Breaking4 so painful to watch. Did anyone who truly understands track & field and human performance think she was going to even come close to running under four minutes? From a best of 4:07, that itself is five seconds faster than any other woman had ever run? For perspective, she’d already shaved nearly 2% off the previous mark.

Of the sport’s all-time greats, only 400-meter hurdle sensation Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone has done better (but over a three-year period and six separate records). Florence Griffith Joyner’s dismantling of the women’s 100-meter record in 1988 is in the same ballpark, but was almost-certainly wind-aided (and possibly drug-aided). Not Mondo Duplantis in the pole vault, not Usain Bolt in the sprints, not even legends Jesse Owens and Paavo Nurmi ever did what Faith has already done.

For comparison, let’s review how the men’s mile record has evolved (and yes, track nerd that I am, I once did a project on this in college). Sure enough, the world’s best of the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics were on par with what Faith is doing today. And no one was yet talking seriously of breaking four minutes.

The 1932 Los Angeles Olympics 1500 Meters

Six men who once held (or would hold) either the mile or 1500-meter (“metric mile”) world records were in Los Angeles for the 1932 Olympics. The Flying Finn Paavo Nurmi (4:10) and the Frenchman Jules Ladoumègue (4:09) were in the Coliseum, but only as spectators after the IOC disqualified them for violating the strict amateur code. Nurmi, arguably the greatest runner of all time, was the first to muse of breaking the four minute barrier, but that was more hype than real talk. None of his other personal bests from his 3:52 1500-meters to his 8:59 two-mile best suggested he had anywhere close to the ability to challenge 4 minutes.

Ladoumègue, who considered Nurmi his role model and hero, won silver in the 1928 Olympics before his banishment and, like Kipyegon, was the first under 4:10 in the mile and 3:50 in the 1500-meters. He also won gold for the most melodramatic commentary about the opening ceremony: “When the runner carries the flame into the stadium, and the birds are freed and all the flags of the world are flying, I cry. I must cry.”

Italian Luigi Beccali won gold in Los Angeles, flashed the Fascist salute from the podium and established a new 1500-meter world record the following year. He was a national hero, but even Mussolini never suggested he could lower his personal best by seven seconds.

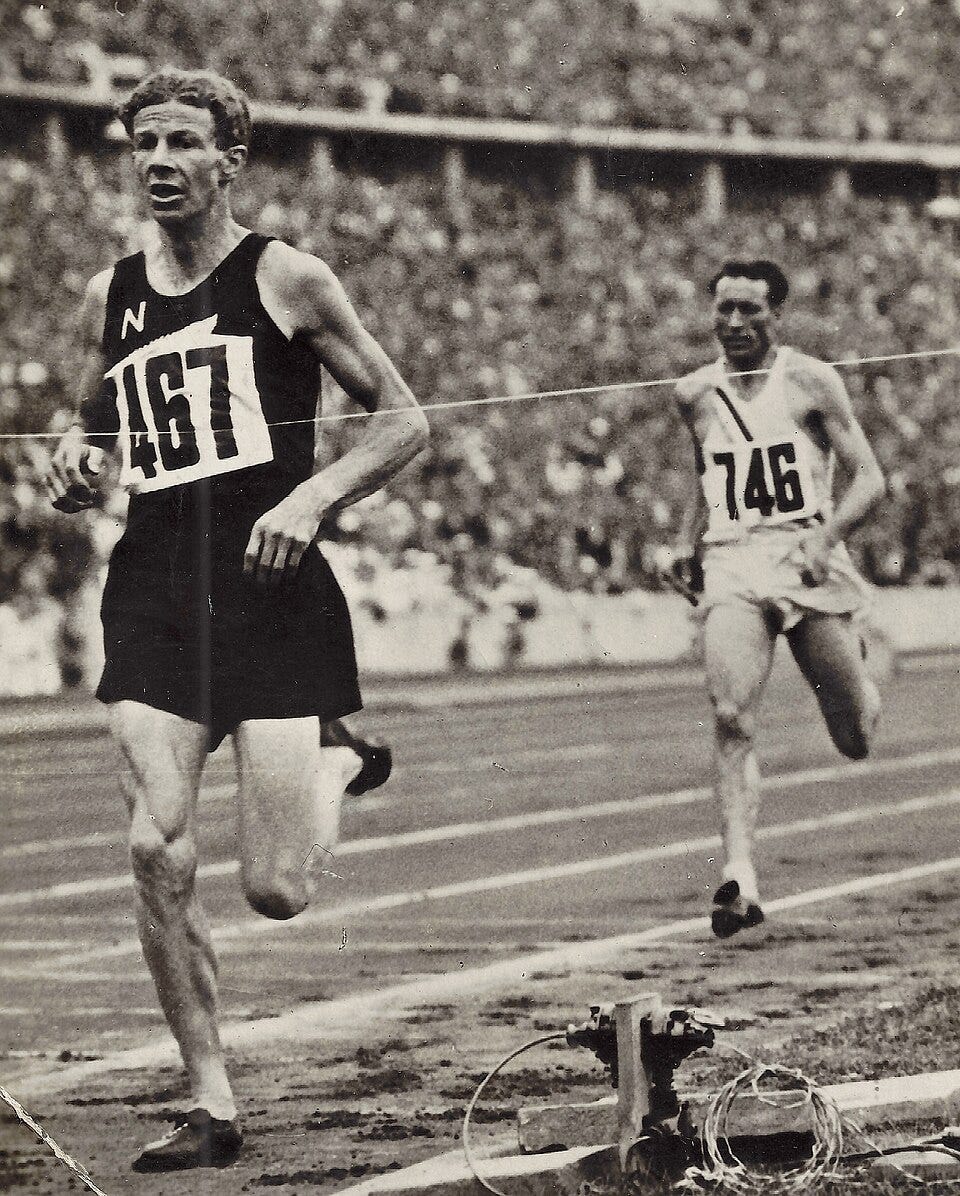

New Zealand’s Jack Lovelock, a former Rhodes scholar at Oxford, finished a disappointing seventh in Los Angeles, but added his name to the list of mile world record holders with his Faith-equaling 4:07 at Princeton’s fast Palmer Stadium track in 1933. He would go on to win gold and set a new 1500-meter world record in the 1936 Berlin Games ahead of American Glenn Cunningham.

Glenn Cunningham, from KU to Dartmouth College

In Los Angeles, University of Kansas star Glenn Cunningham led with 300 meters to go but, battling a cold, faded to 4th. Badly burned in a schoolhouse fire when he was seven, Cunningham was fortunate to ever walk again on his badly-scarred legs, let alone become one of America’s all-time-great milers. Under the tutelage of KU (and future Cal Berkeley) coach Brutus Hamilton, he became one of the era’s most consistent performers, setting world records in the mile (4:06.8) and 800 meters (where he dethroned Stanford’s Ben Eastman) in 1934, and winning an Olympic silver medal in 1936. But his most memorable performance—and most like Breaking4—came at Dartmouth College in 1938.

Hanover, New Hampshire is as unlikely a place as any to have the “world’s fastest track”, but that’s exactly what long-time track coach and athletics innovator Harry Hillman boasted in the 1930s. He had a point. When Dartmouth built Alumni Gym in 1909 the college laid out an oversized 6 2/3 laps-to-the-mile indoor track with two 100-yard straightaways that tunneled between wings of the massive complex. Already larger than the 11-laps-to-a-mile tracks in New York and Boston, the Dartmouth oval became the world’s fastest in 1932.

With Hillman’s prodding, Thayer School of Engineering Professor Howard Lockwood designed a fast track that the Superintendent of Buildings & Grounds Willard Gooding proceeded to make even faster. Gooding laid 1 1/2” highly-flexible spruce boards on top of a forgiving cinder surface and built three-foot-high banked turns at a 30-degree angle (versus the traditional 20-degree slope or maximum 18-degrees of today’s tracks). Dartmouth athletes had consistently run their best times on their home track and now Hillman wanted to prove it was no fluke.

As reigning indoor world-record holder, Cunningham was the perfect man for the job. On the evening of Thursday March 3, 1938 a reported 3,000 students and townsfolk—Dartmouth’s student body totaled 2,440— packed the gym. And unlike the smoke-filled Garden races in New York and Boston, the air was fresh inside after spectators were asked to leave their cigarettes at the door.

Six members of the Dartmouth track & field team took turns pacing Cunningham with the college’s top miler, Stu Whitman ‘38, taking him through quarter-mile splits of 58.5 and 64 seconds before stepping off the track. Wearing a NYCE (New York Curb Exchange, the precursor of the American Stock Exchange) Athletic Club tank top, the Kansas great upped the pace to 61 and 60 seconds over the final half-mile to finish in 4:04.4. He had run two full seconds faster than the existing outdoor world record, and although the pacers had made the run record-ineligible, his performance got experts a bit closer to saying “four minutes flat” aloud. For his part, Glenn thought he maybe had two more seconds in him.

Sub-Four Will Probably Happen, Just Not Soon

Brown University’s Norman Taber won bronze in the 1912 Olympic 1500-meter race and in 1915 claimed the mile world record (4:12) on Harvard’s track (albeit it in an exhibition handicap race that would not be record-eligible today). It took 18 years (and three different men) before the record fell to 4:07, the same leap that Faith Kipyegon achieved in a single attempt. And how soon after that did the world marvel at Roger Bannister’s legendary sub-four? Twenty-one years. Yes, WWII impacted activities as superfluous as athletics (leaving two Swedes named Gunder and Arne to alternate holding the record six times in their neutral, wink wink Nazi, homeland). But the point remains. It takes time, heated competition and future generations to emerge for such monumental improvements in human performance.

After Kipyegon’s Breaking4 attempt, reputable news outlets featured head-scratching headlines: “Faith Kipyegon…

Almost Broke the 4-Minute Mile” - Outside Magazine

Nearly Breaks Four Minutes” - FloTrack

Falls Agonizingly Short” - The Independent

Really?

Faith should absolutely be celebrated for all she has achieved and for attempting something I’m guessing even she knew she had no chance of succeeding in from the start. We should take a moment to reflect on the heights she has already attained. And not get too far ahead of ourselves.

She is the greatest of all time, but she will not break the four-minute barrier. It’s more likely that the woman who will break 4 hasn’t been born yet (barring some Nike-inspired pogo stick invention I can’t see how this record gets lowered by over 7 seconds anytime soon). Records are, as the saying goes, meant to be broken. But they also follow relatively predictable patterns between men and women and across distances. Going from 4:12 to 4:07 to 3:59 in quick succession is not one of them. Not in the 1930s, and not in 2025.

Josh nails it—Kipyegon’s a legend, but sub-four isn’t around the corner. Progress like that takes generations, not headlines.

Great piece, Mr. Hanna. I was surprised when the hype started for her potentially breaking the 4-minute mile - magical thinking and someone at Nike's willingness to try and sell some product and set up the agony of success!