Stanford's "Big Ben" Eastman

1932 Los Angeles Olympian was once the world's best 400/800-meter runner

Part 1 of 2

Ninety-three years ago today, on a warm, windless Saturday afternoon in Palo Alto, California, Stanford University junior Ben Eastman ran what the Los Angeles Times’ Braven Dyer breathlessly called “the greatest race ever run by human legs.” He had amputated a full second from the 16-year-old quarter-mile world record in his first race of the season. And he was just getting started.

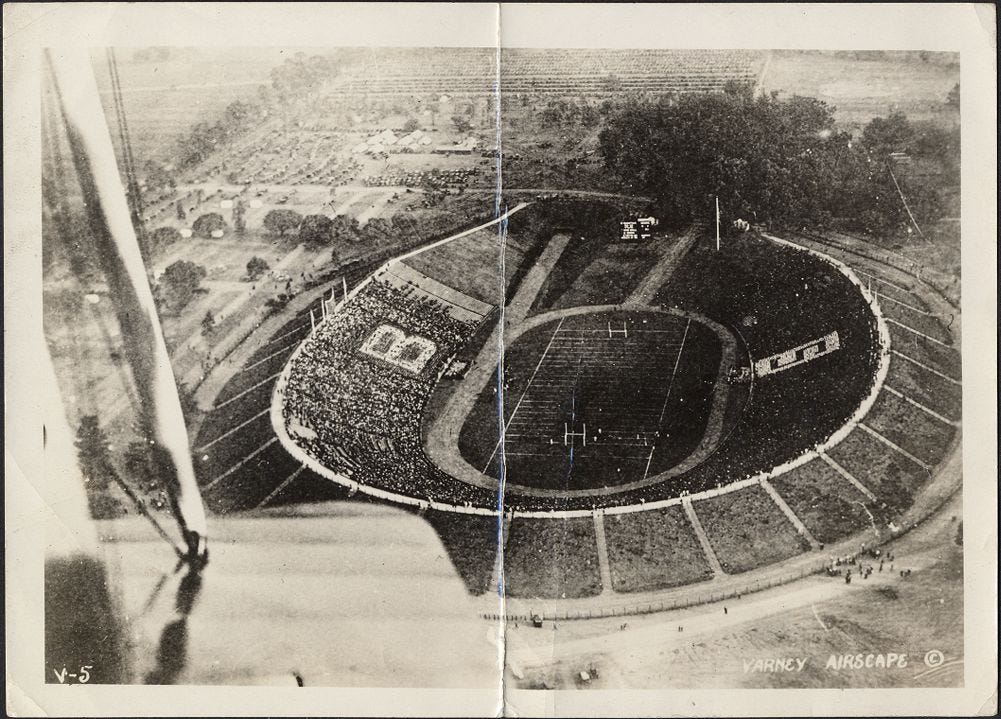

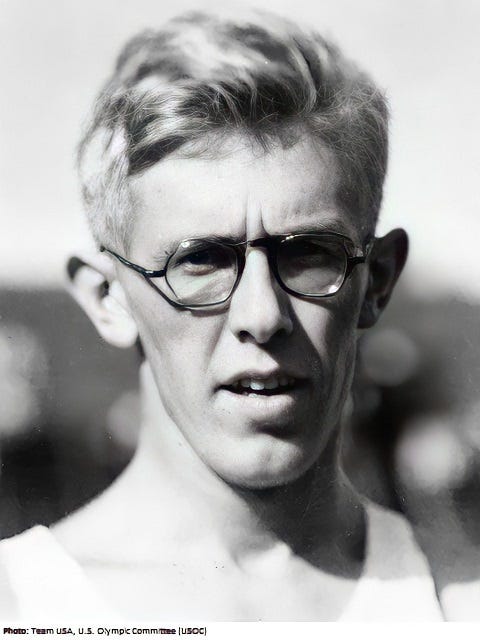

On that late-March afternoon, 5,000 spectators crowded around the old Stanford Oval (renamed Angell Field the following year) to watch their team take on the Los Angeles Athletic Club (LAAC). But it was the fourth event on the program, the 440-yard dash, that garnered most of the interest. And all eyes were on the bashful “begoggled blond”, the 6’1”, lanky, 155-pound runner with the protruding ears. A former Burlingame High School star who joined the track team to meet a school physical fitness requirement, Ben initially tried the long jump while his older brother Sam tackled the high jump. He performed admirably in a range of events, but he soon discovered his talent lay in the long sprint. A world-record-equaling 47.4-second quarter-mile run in the Los Angeles Coliseum his sophomore year at Stanford confirmed it.

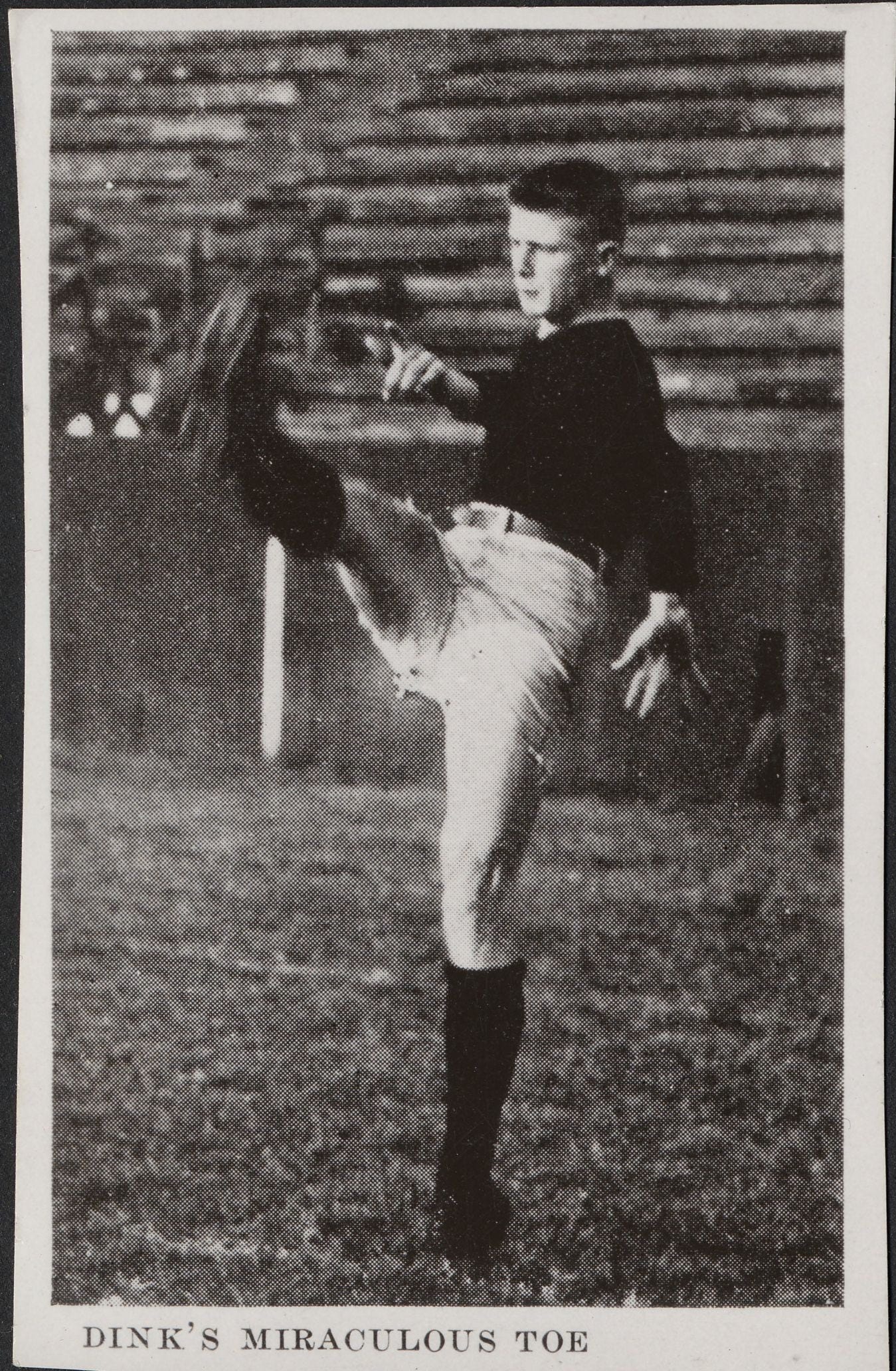

Five minutes before his record attempt, Eastman was summoned to the press box to take a phone call. Thirty-five miles north and bedridden for months with “acute arthritis” at the Stanford Lane Hospital on the corner of Clay and Webster Street in Pacific Heights, Eastman’s coach was calling in with last-minute instructions. Palo Alto High School and Stanford University alum, Robert Lyman “Dink” Templeton, had competed in the 1920 Olympics in both the long-jump and rugby competition in which his United States team upset France for the gold, in part behind his 50-meter drop goal. Templeton had been an all-around great athlete but with Stanford, and many west coast universities, eschewing the increasing violence of American football in favor of rugby from 1906 until 1919, he first honed his kicking skills in the older European game.

Dink had coached at his alma mater for ten years, but he’d never had an athlete quite like “Blazing Ben”. He told him to forget that he was going after a record and to just relax. Interesting advice given that Dink had changed the way runners approached the quarter, running it as a pure sprint—“get out in front and stay there” he was credited with telling his athletes. It made sense in the days of panhandle tracks (so named because they resembled a pan—the oval—and handle—the long straightaway) when quarter-milers did not run in lanes, but instead made a break at the curve after a furious 220-yard dash down a long straightaway. It was a more tactical and, at times, physical race than today’s 400-meter runs; akin to the two-lap, mad break for pole position witnessed in today’s indoor 400-meter races.

On that early spring afternoon in 1932, Eastman was last to leave his starting crouch. But by the time he hit the turn with his long, loping strides he was 10 yards clear of his three competitors. Some in the press box clocked him at 21.3 seconds at 220 yards, faster than his personal best over the furlong. On the curve he disappeared from view behind temporary bleachers on the infield, but as he emerged down the home straight the crowd knew something special was afoot. Twenty yards from the tape he started to strain, as any full-send quarter-miler does, and with just five yards left it appeared he had “shot his bolt”.

But he hung on. James Gordon of the LAAC and future 1932 Olympic finalist was 15 yards back. Three of the four timers clocked Eastman at 46 and two-fifths seconds (46.4 in today’s digital parlance). The fourth had him at 46.5, but majority ruled in the less-than-perfect days of hand timing. All were sheepish in sharing the result, so mind-boggling was the time. It would soon be recognized as a new world record, his second after his Stanford team’s mile relay record from a year earlier.

The Cocksure, Unorthodox Coach

Interviewed after the race, Ben was his usual modest self. But Dink was never shy in shouting out his athletes, boasting that Eastman would run a half-second faster in the quarter, if only he had someone testing him down the finishing stretch, and become the first man under 1:50 in the half-mile. When asked about his star’s potential, Templeton was nonchalant: “I want Ben to crack the records early in the season and get them off his mind so that he can be used in any race we see fit.” He continued, “he has a lot of points to score in several meets”, meaning his star would be running three races and anchoring the mile relay to help his Stanford team most weekends.

Such a heavy racing load would weigh on most athletes. But Dink claimed Eastman was different. Just two weeks after his other-worldly 440-yard run, Ben grabbed his second record, running 1:51.3 for 880 yards. Like all his record-breaking attempts, he shot to an immediate lead and ran unchallenged from the front.

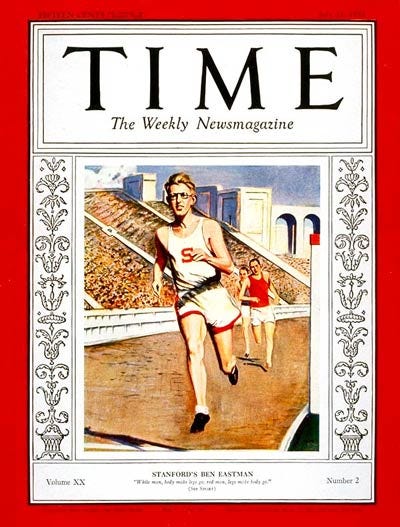

Templeton, described in a Time Magazine article as “redheaded, squint-eyed and friendly”, was known for his intense training regimen—Eastman began working out in October and started on a steady diet of 220-yard sprints in January—and often unorthodox methods. Commenting on his 6’2” sprinter, Hector Dyer, Dink said he looked “like an ostrich struggling to get going”. Perhaps that explains why he once studied ostriches’ leg motions in hopes of helping his tall sprinters—Eastman among them—improve their starts.

Willing to try anything for an edge, Dink placed bricks under Dyer’s hands in practice to elevate his starting position by a few inches. They appeared to help, so for the next race he cut 4”x4” wooden blocks which he secured to the track with a long spike. After using starting blocks for both hands and feet at the “Big Four” meet between Stanford, Cal, UCLA and USC in Los Angeles in the spring of 1929, Stanford had run away with the title but were disqualified after USC coach and rival Dean Cromwell argued that the blocks were unfair. The NCAA later ruled that the hand blocks could be used on a one-year experimental basis in 1930, but they never caught on.

Kezar Stadium: San Francisco

Half-milers of the era started races in a sprinters’ crouch position, but Eastman wasn’t using Dink’s odd hand blocks on June 4, at the 1932 Pacific Association Championships, when he set out to lower his own half-mile world record. Given permission to leave his hospital bed to watch the race, Templeton was impressed with his star’s power running against the swirling winds. After an opening 53-second split, Eastman raced through two separate finishing tapes strung at 800 meters and 880 yards (4 1/2 meters apart), eclipsing the accepted records in both with his 1:50.0 and 1:50.9. Neither time was ever ratified as a record, bizarrely, because they were deemed “wind-aided”. True to form, the coach who the Pasadena Post called “arrogant and blustering” told reporters afterwards that Eastman could have run 1:48 in calm conditions. There was nothing he lacked, Templeton said, “except competition”.

Fresh off becoming the first man since the University of Pennsylvania’s Ted Meredith in 1916 to simultaneously hold both the quarter and half-mile world records, Time featured the Stanford star on its cover in the weeks leading up to the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics. He seemed to be a lock for Olympic gold. The only question left unanswered was: which event, or both?

Next week we’ll pick up Ben’s quest for Olympic gold and meet “Wee Willie” at the IC4As, held in July 1932 at newly-opened Edwards Stadium in Berkeley.

Hand blocks nailed down to the track, studying ostrich leg motions, gotta love Dink's ingenuity! I love how Ben went from fulfilling a simple fitness requirement to shattering world records!

fascinating! what did he do in later in life?