Podium

How the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics created a verb

po·di·um /ˈpōdēəm/: (of a competitor) finish first, second, or third, so as to appear on a podium for an award.

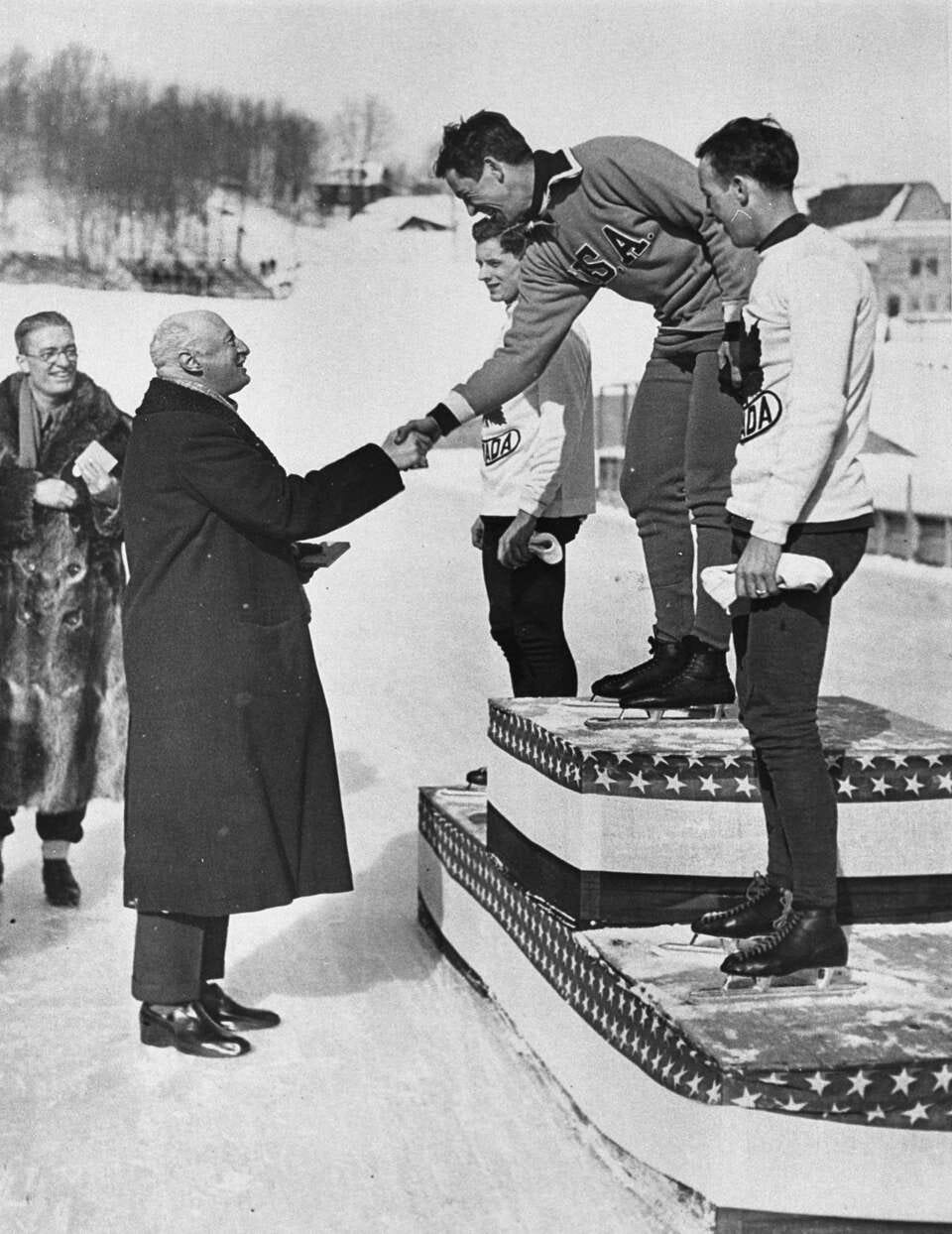

February 4, 1932: One small step (up) for a Dartmouth College sophomore, one giant leap for Olympic pageantry. Minutes after 21-year-old speed skater and Lake Placid, New York native Jack Shea won the 500-meter race in front of his hometown fans at the III Winter Olympics, he became the first Olympian to receive his gold medal from, what newspapers of the day called, the “victory stand”.

Earlier on this twenty-degree winter morning, he’d taken the amateur oath on behalf of 250 athletes representing 17 countries and, to the Adams Empire Band’s rendition of the Star Spangled Banner, marched in front of New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt, opening the games for the no-show President Hoover. But it was Shea’s step onto the wooden podium, still in his skates, that made history. (British figure skater Mollie Phillips made her own Olympic history that day, leading the UK’s four-woman delegation, marking the first time a woman carried her nation’s flag at an opening ceremony).

The Olympic medal ceremony of the early twentieth century bore little resemblance to today’s tear-jerkers. Kings and Queens stood on raised platforms and handed medals down to all the athletes at the closing ceremonies, assuming they were still around, which they often weren’t. Godfrey Dewey, son of Amherst College’s Melville Dewey (of Dewey Decimal System fame), led the Lake Placid organizing committee, but the podium was not his brainchild. That came from another Melville.

British Empire Games

Inspired by the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics, Melville Marks Robinson, a Canadian journalist and sports executive, organized the first-ever British Empire Games in 1930 (known since 1978 as the Commonwealth Games). Eleven teams including Newfoundland competed in six events from athletics to lawn bowling. IOC President Henri Baillet-Latour travelled to Hamilton, Ontario to watch and he liked what he saw, particularly the introduction of a podium for victory ceremonies. In May 1931 Latour went one step further, instructing the two 1932 Olympic hosts to present medals to athletes as their flags were raised and the winner’s national anthem played from loudspeakers. The directive even specified podium positions—gold medalist in the center, silver to their right and bronze to their left. The medal ceremony had become official protocol.

Los Angeles Adds a Hollywood Touch

Jack Shea made Olympic history, but Los Angeles made the medal ceremony what it is today. Lake Placid was a small village of 3,000 and the Winter Olympics were in their early stages of development. There was only so much fanfare a wintry environment could provide. But Los Angeles was different.

Inside the Coliseum with tens of thousands of adoring fans, athletes stood atop podiums—now marked 1-2-3—and watched as three flags ascended the peristyle and the winner’s anthem rang out from the loudspeakers. It was truly a Hollywood-worthy production.

The first to be so honored was the French weightlifter and Parisian dance instructor Rene Duverger. He’d earned his moment in the spotlight the evening before in the Olympic Auditorium, but realizing the spectacle that large crowds provided, officials decided to award all medals in the grand Coliseum.

From Ancient Greek to American Slang

The Olympic podium may have arrived in 1932, but no one called it that yet. Podiums were still just pedestals that orchestra conductors stood on. Fittingly, the word comes from the ancient Greek podion which means a “small foot” or “base”. From that came the Latin podium—“a raised platform”—which made its way into the English language beginning in the 18th Century.

The verb to “podium” first came into use at the 1948 London Olympics and gained traction in the decades to follow. While most common in the United States, other English-speaking nations have begun to favor the term as well. But its use remains controversial in some literary circles.

The dream of so many athletes—to podium in sporting contests—has its roots in the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics. Just watch any battle for third place at the end of a marathon or track meet to appreciate its meaning. First is best but, so often, fourth is worst.

I'd love to learn the history behind the advent of "Podium Girls" in the Tour de France. Maybe for your next book.

I had no idea! Thanks once again Josh....