"It Ain't Bragging If You Can Back It Up." - Muhammad Ali

Mildred "Babe" Didrikson: the Ali of her day and star of the 1932 LA Olympics

For the first time in Olympic history, athletic participation at the 2024 Paris Games reached gender parity. It would have made the French founder of the Modern Games Pierre de Coubertin’s head explode. Mildred “Babe” Didrikson’s performance and swagger in the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics undoubtedly did as well. A generation before Muhammed Ali would shock the world with his brash “I am the greatest” boasts, Babe demanded the spotlight and told anyone within earshot that she would beat them all.

Women were not welcome in the Ancient Olympics—not even as spectators—nor did they participate in the first Modern Games. Coubertin was unapologetic in his views, claiming that a woman’s only role was to “crown the winner with garlands”. Ten years later, despite reluctant inclusion of a few women’s events deemed “lady-like” by the IOC, he made no attempt to disguise his objections to what he called “the indecency, ugliness and impropriety” of female participation in sports. Women who engaged in strenuous activities were “destroying their feminine charm and leading to the downfall and degradation of sport.”

Citius, Altius, Fortius

Ironic, then, that the biggest star of the 1932 Olympics was not only a woman but a cocky, young athlete with short-cropped hair and a Texas twang who, more than any other, embodied Coubertin’s Olympic motto Citius, Altius, Fortius—Faster, Higher, Stronger—by running, jumping and throwing her way to Olympic immortality.

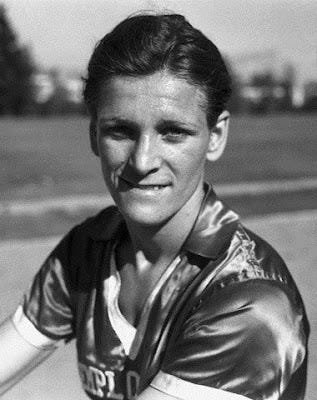

Babe was a “wiry lass,” a muscular, 130-pound athlete who Don Van Natta Jr., one of her many biographers, described to a tee as: “not glamorous, but her face was striking and intelligent, with impish hazel eyes, a hawk nose, and a slightly crooked, thin-lipped grin (who)… walked with a champion athlete’s loping gait.” She had been called homely, boyish, and even “hatchet-faced” by well-known New York Daily News sports columnist Paul Gallico. He may not have liked Babe and what she represented, but he sure couldn’t stop writing about her.

Even before the Olympics, Babe became a legend, single-handedly winning the team competition in the 1932 AAU Championships, doubling as the Women’s Olympic Trials. Competing in 8 of the 10 events, she won 5 including 3 to be contested in Los Angeles. Had there been a women’s heptathlon at the time, she would have embarrassed the field even more than world record holder Jackie Joyner-Kersee would decades later. In lists of all-time female athletic greats, only Kersee consistently ranks ahead of Babe.

Babe’s First Olympic Gold

As late afternoon became early evening on the first day of track & field competition, Babe took center stage in the women’s javelin—and never relinquished the spotlight. Athletics had been the centerpiece of the Ancient Olympics, as they have remained in the Modern Games. And perhaps no event was more iconic than the javelin. First contested in 708 B.C. as part of the pentathlon, the javelin represented the classic male warrior. It was fitting, then, that Babe, whose mere presence angered much of the male IOC establishment, would make her debut in such an event.

On the first of her three throws, she took several short, halting steps before letting the seven-foot, steel-tipped birch spear fly from the throwing arc. It sailed through the air in an unorthodox low arc, more like a baseball thrown by an outfielder. This wasn’t surprising—she held the world record in the baseball throw as well (an AAU event women contested until 1957). Her javelin win made her the first American woman to receive a gold medal atop the podium while the national anthem played and the Stars & Stripes fluttered in the breeze.

“She inspired either great enthusiasm or great dislike”

Only 127 women competed in track & field, swimming & diving, and archery in 1932—a small enough contingent to house at the five-story Chapman Park Hotel on Wilshire Boulevard, away from the male athletes at the Olympic Village. According to their Official Report, Olympic organizers “felt that feminine needs could be more completely met in some permanent type of residence.” Women of fourteen nations slept two or three to a room, ate together in the restaurant, and mingled in the lounge and at afternoon tea in the garden. A genuine camaraderie blossomed, just not with Babe, who grated on many a nerve. At a time when athletes (especially female) were expected to be humble and modest she was anything but—always needing to be the center of attention and bragging about how she would beat everyone at everything.

Teammate Evelyne Hall remembered Babe being “cocky… full of herself… a braggart” while team captain Jean Shiley said she had “no social graces.” Others have suggested that her arrogance masked underlying anxiety. An ugly incident with one of her Black teammates highlighted a still darker side, but Babe was never shy about hiding her racism. A product of Beaumont, an east Texas town dominated by the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, she once crowed about beating up Black children in her neighborhood.

Her Second Gold

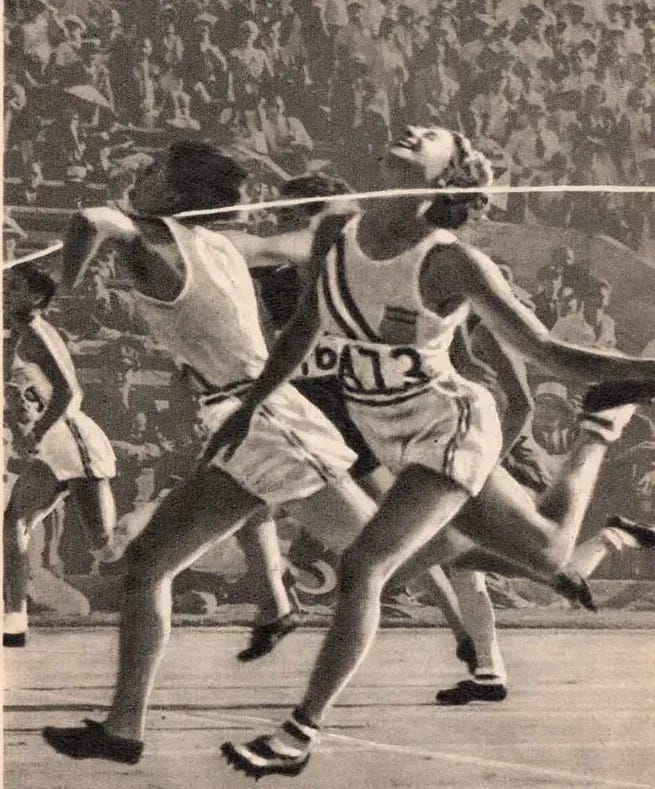

Four days after her javelin win, Babe won the 80-meter hurdles in a race reminiscent of the too-close-to-call men’s 100-meters final. Teammate Evelyne Hall appeared to draw even at the tape, throwing her head back just as Babe raised her arms slightly and twisted her torso to the right—a motion that often swayed the opinions of finish-line judges.

Before they had even come to a stop, the two shook hands. The verdict was still very much in doubt to everyone in the Coliseum—officials included—except the outwardly-confident Babe. As another finalist told it, Babe was “very confident. She just knew she was going to win everything.” Babe raised her arms, embraced her sister, and told Hall she had won, but Hall’s friends were telling her she’d won. The cut on her neck left by the finishing yarn made her believe that they might be right. After a thirty-minute delay, the judges awarded Babe the gold and Hall the silver in what Arthur Daley called an “eyelash victory.” Babe’s quest for three golds was still alive.

Settling for Silver but Building Her Legend

The dust had not even settled before Babe was announcing to the newsmen: “I’m going to the high jump Sunday and set a world’s record.” It was bold, arrogant, and 100% Babe. She had opened the competition with a victory and now on the eighth and final day of the Olympic track & field program she intended to close them with her third gold medal. Who would doubt her?

The 5’10” Jean Shiley for one. They had tied in the Olympic Trials and were tied again in Los Angeles heading to a jump-off. Though her teammates and even the US coach exhorted Shiley to call out Babe’s illegal “diving” style in which she cleared the bar head and shoulders first, rather than the approved feet-first method, Shiley would have none of it: “You don’t beat Babe by claiming a foul. You just don’t. It would have been murder.” But the judges eventually disallowed Babe’s clearance. Her pursuit of a third gold ended, not by her athleticism, but by style. It was the correct call based on rules of the day, but it didn’t stop the newsmen, increasingly enamored with Babe’s sporting feats and charisma, from crying foul.

Already an All-American basketball player, Babe would go on to dominate women’s golf in the 1940s on her way to induction in three separate sports Halls of Fame. A plaque on the wall of honor in the Los Angeles Coliseum commemorates her Olympic accomplishments—the first woman so honored. There can be little wonder why the Associated Press voted her best female athlete of the half-century in 1950, only six years before her untimely death at age 45.

You Can’t Win, So Win

As we honor International Women’s Day this week and Women’s History Month this March, I am reminded of Nike’s recent Superbowl ad featuring a cast of star female athletes: “You Can’t Win, So Win.” Bill Maher, a comedian with whom I typically agree, called the whole premise of Nike’s ad a “zombie lie”—something that used to be true but no longer is true. But is it really?

While women’s sports have reached heights unimaginable a century ago, some stereotypes have proven stubbornly persistent. During the 1932 Olympics, Kansas City “cosmetics king” Thomas Luzier said there was no Depression in lipstick sales as “there is never a depression in a woman’s effort to become beautiful or to preserve her beauty.” In 2024 veteran British sports commentator Bob Ballard made headlines at the pool when he said of the Australian female relay swimmers: “Well, the women just finishing up. You know what women are like … hanging around, doing their makeup.”

In 1932, most of the women’s swimmers and divers—“mermaids” as they were branded—were asked by sportswriters about their marriage plans. In 2021, a CCTV reporter asked newly-crowned Olympic shot put champion Gong Lijiao, who they called a “manly woman”, about her plans for marriage and having children—or as they asked her, do you have “any plans for a woman's life?”

Then and now, female athletes are routinely described as “emotional” alongside, and sometimes instead of, accounts of their athletic accomplishments. Much has changed in the last century, but not everything.

Ali was the greatest and said so. So did Babe.

Impressive athlete, love the bravado, yet trying to square the competitive athlete with the racist person...I don't look to my athletes for political opinions nor expect them to be role models (shush Charles Barkeley), but it you're going to crow about something, I'd say let it be your athletic accomplishments and not how you beat up black kids in your neighborhood...

She'd be HUGE today (with endorsements and stuff). She was ahead of her time, I think.