A few of you have asked me if LA28 might be moved to another city following the mass destruction caused by the ongoing wildfires. Given the loss of life and property damage estimated at $150 billion or more, it is a fair question. Comments by conservative influencer Charlie Kirk and Representative Jim Jordan (R-OH) calling for the Games to be moved to a Republican-run city such as Dallas or Miami have undoubtedly fueled the speculation.

But it’s not going to happen for several important reasons:

That’s not how the process works. If Los Angeles or the IOC decided that the city was no longer prepared to host, the decision on where to move the Games would be entirely up to the IOC and its members.

The IOC is not exactly flush with cities begging to host as they were in the past. When the IOC awarded the 2024 Games to Paris in 2017, they took the unprecedented step of awarding Los Angeles the 2028 Games at the same time. Hosting a Summer Olympics is no small feat and LA is uniquely positioned with its existing infrastructure, including the Coliseum which will become the first stadium to open three Games.

None of the 2028 venues were damaged in the fires. The horrific Pacific Palisades fire threatened the Riviera Country Club where golf will be played and concerns were raised about the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, but neither was lost.

There is no precedent for moving the Games. Although the Olympics have been cancelled on three occasions due to World Wars I and II (1916, 1940, 1944), and postponed a year in 2020 due to the global Covid-19 pandemic, Denver (1976 Winter Olympics) remains the only city to have been awarded the Games and subsequently back out. And that was due to taxpayers concerns and a municipal referendum, not a disaster.

LA28 Chairman Casey Wasserman, Governor Newsom and President Trump have all stated publicly their commitment to hosting the games as planned.

Barring another unforeseen, major catastrophe in Southern California, I do not see a scenario in which the Games are moved. I say this based on the above points and an historical perspective.

Disaster before the 1932 Olympics

Water, specifically, not enough in some hydrants, was a major topic of discussion regarding the recent fires. But in the run up to the 1932 Olympics too much water was a major problem.

Angelenos insatiable thirst for growth—and water—has not been without controversy and tragedy. The Owens Valley/Los Angeles Aqueduct has supplied water from 233 miles away to the ever-expanding city since 1913. But when existing storage capacity proved insufficient, work began in 1924 on a massive new reservoir just forty miles from downtown.

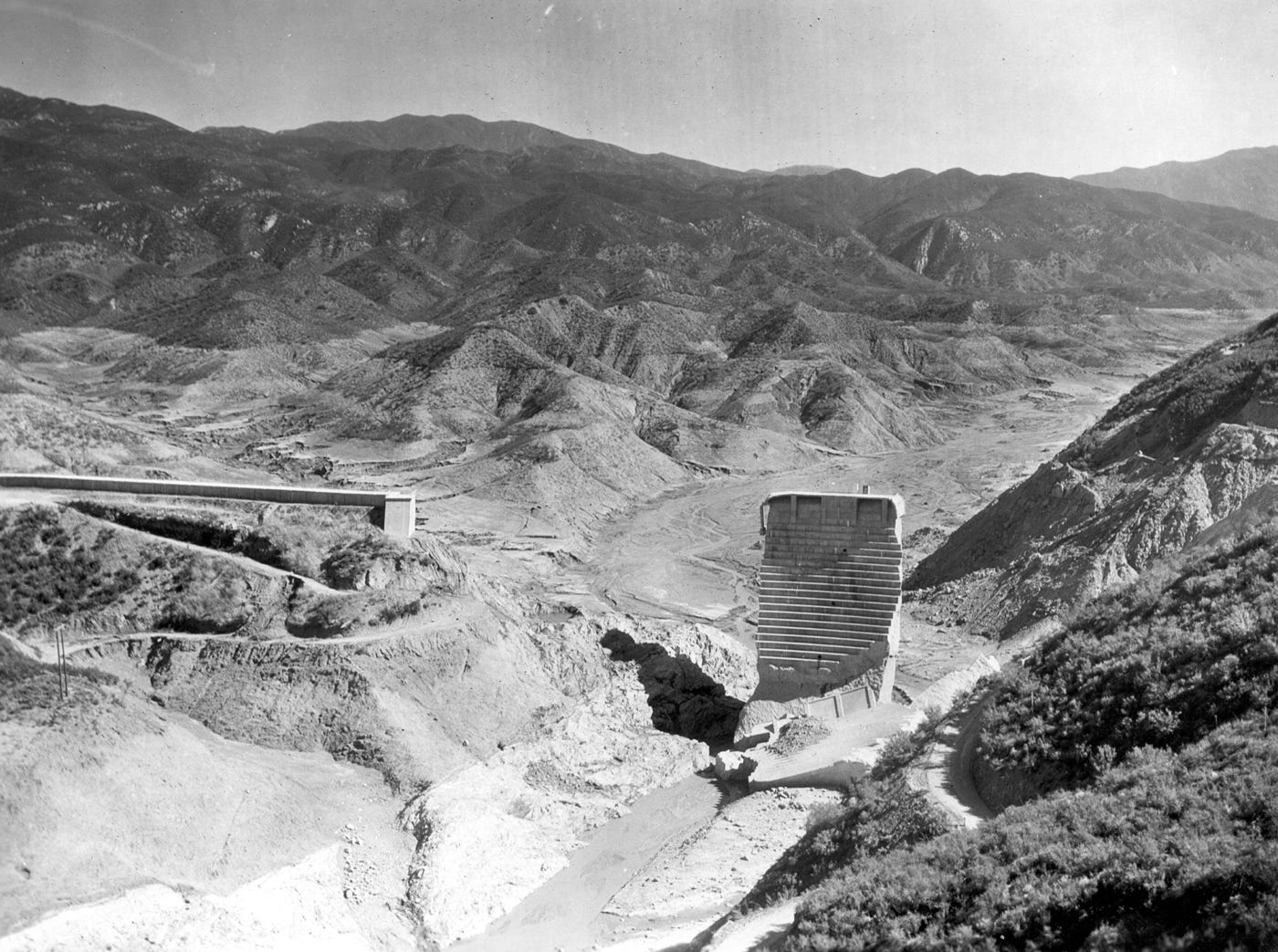

Two years after completion of the St. Francis Dam, and mere hours after Chief Engineer William Mulholland of the Bureau of Water Works and Supply had personally inspected it, the 200-foot-tall concrete dam collapsed shortly before midnight on March 12, 1928. A 140-foot wall of water, more than 12 billion gallons, tore through San Francisquito Canyon at eighteen miles per hour. Twelve-hundred homes were destroyed. Most of the 425 people, including 100 children, killed in the deluge never knew what hit them. The flood traveled some 55 miles before emptying into the Pacific Ocean between Ventura and Oxnard. Bodies washed ashore as far away as Santa Catalina Island.

After the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, it ranks as California’s second deadliest disaster. It was the worst civil engineering accident in American history until the levees broke in New Orleans. The tragedy marked the end of Mulholland’s illustrious career but did little to stop the city’s expansion. Massive new water projects in Mono Lake and the Colorado River were supported by equally-massive bond measures in 1930-31.

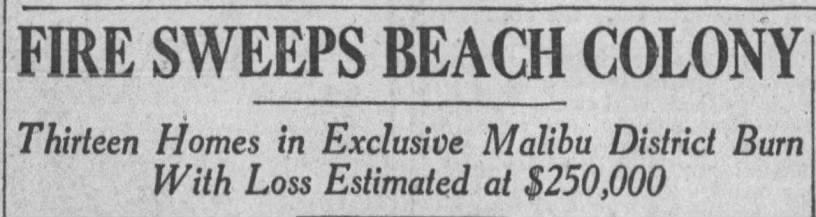

Before that, wildfires hit Malibu in 1929, destroying valuable beachfront properties.

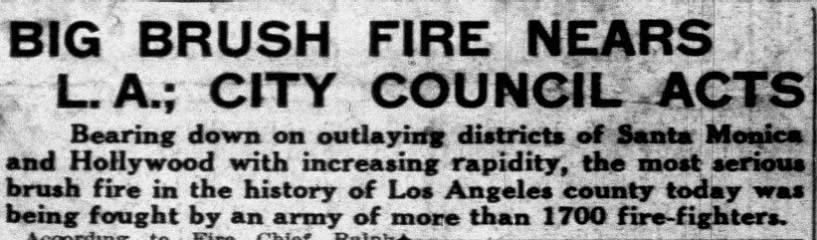

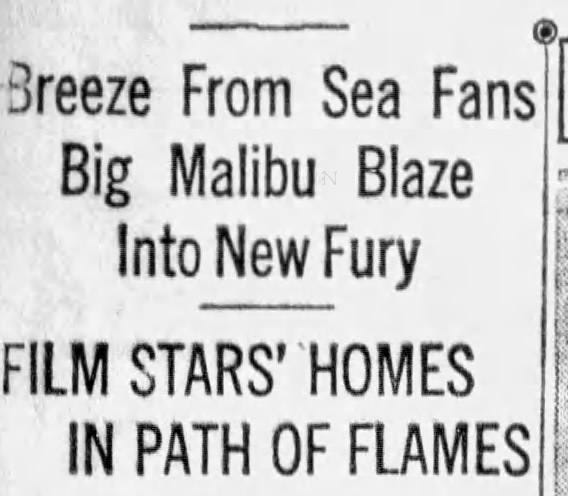

And again the next year, when walnut pickers in Thousand Oaks accidently started a fire that the Santa Ana winds pushed toward Pacific Palisades. More than 44,000 acres burned between Ventura and Los Angeles Counties in what was then the “most serious brush fire in the history of Los Angeles county.” More than a thousand fire fighters could do little more than look on before the winds mercifully subsided, sparing the city further tragedy.

Then Comes the Great Depression

An Olympics awarded to Los Angeles in the Roaring Twenties, was held in the depths of the Great Depression. On September 3, 1929 the Dow Jones Industrial Average closed at a record high 381. By the summer of 1932 the U.S. stock market had plummeted 89%. Unemployment hit 25% as migrants exacerbated an already desperate situation. Hungry Angelenos lined the streets at soup kitchens while thousands huddled in Hoovervilles on the edge of the city. Suicides spiked 50%. On the day of the opening ceremony, sixty-year-old H.P. Knight jumped to his death off the 10th floor of the downtown Hollingsworth Building. Investigators cited “financial reverses”.

Protesters demanded the Games be cancelled, picketing at the State Capitol with signs that read “Groceries Not Games”. IOC member Sigfrid Edström publicly questioned the sanity of moving forward as planned. President Herbert Hoover declined to attend. And just five months before the opening ceremony, not a single country had agreed to send athletes.

And yet, the 1932 Olympics were not only held but would prove to be a wild success. Record attendance, record-breaking performances by athletic trailblazers, innovations that would become part of the Olympic tradition, and ultimately, a tidy profit followed.

The Olympics have faced other difficult periods, notably the Munich hostage tragedy in 1972, the financial disaster of Montreal in 1976, and the U.S.-led boycott of the 1980 Moscow Games. But as in 1932, Los Angeles helped to revive the Movement in 1984, despite a tit for tat Eastern Bloc boycott led by the Soviet Union. Through Peter Ueberroth’s savvy mix of exclusive sponsorships and lucrative television rights deals LA84 would be the first to repeat what 1932 organizers had achieved—turn a profit. In spite of all the re-building to come in the next few years, I wouldn’t bet against LA28 doing the same.

Great post! I’m always fascinated by major upsets, especially in distance running and swimming. Stories of overcoming significant obstacles are always inspiring and exciting to learn about—no matter the sport! Keep it going.

Timely, places the current situation in context. The New York Times should reprint this, so the whole country can read it. For more on water and Los Angeles history, this NPR Throughline podcast is pretty good:

https://www.npr.org/2026/01/01/1198920684/throughline-water-in-the-west-behind-the-scenes