Soldiers in the streets of Washington, DC

Two days before the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics opened

July 28, 1932: The bullet tore through the immigrant’s back and lodged in his pelvic cavity. Thirty-eight-year-old Eric Carlson of Oakland, California had come to America from Sweden. He enlisted in the Army just weeks after the United States entered World War I, served for more than a year in France with the 76th Field Artillery, and survived a German gas attack and shell shock. But more than a decade after he endured trench warfare, he was killed by a Washington, DC policeman for protesting against the country he served.

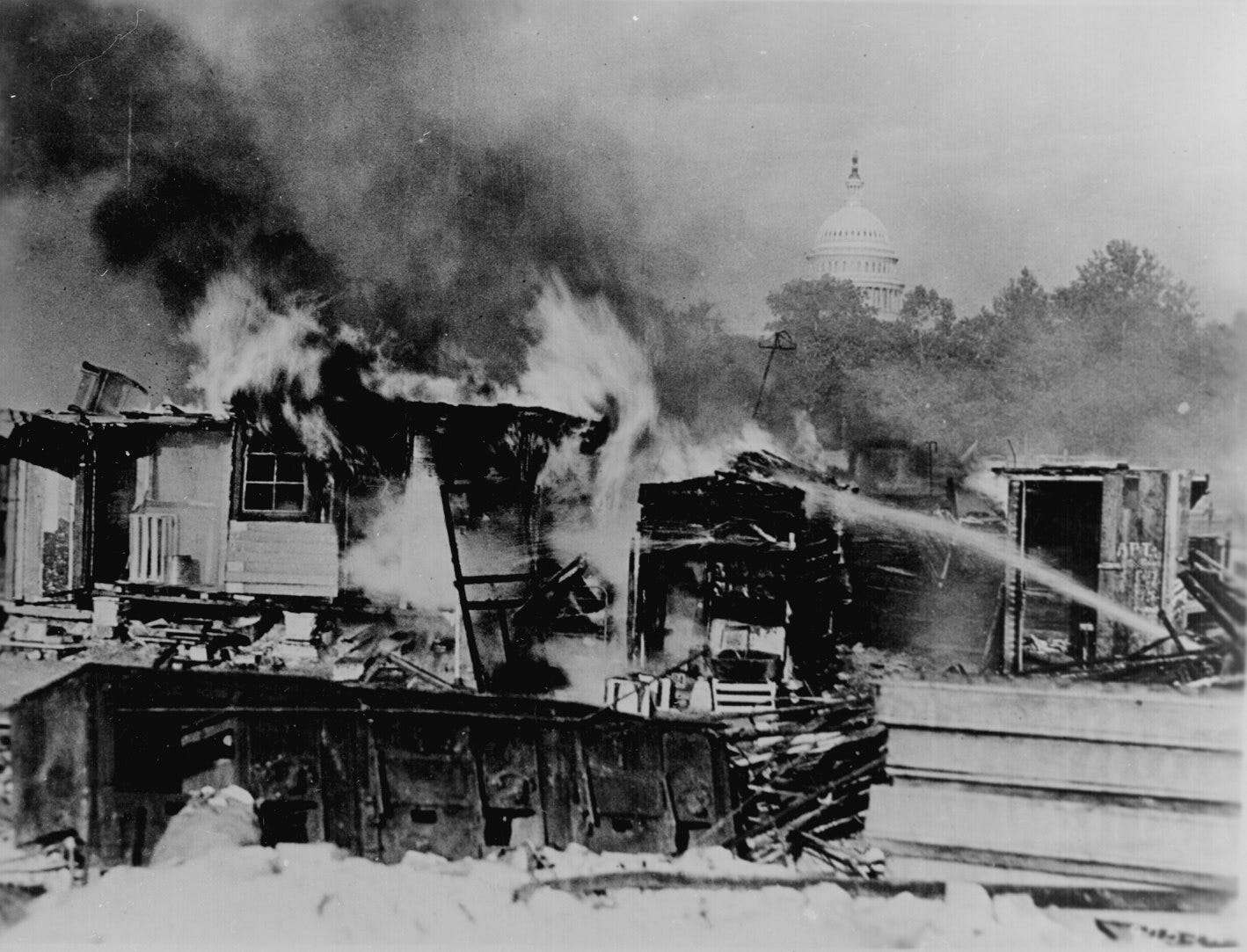

Two days before the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics opened, President Herbert Hoover asked his Secretary of War to deploy soldiers in the forced removal of nearly 20,000 World War I veterans. Dubbed the “Bonus Army”, the desperate men had encamped throughout the city—in abandoned Federal buildings and in shanties along the Anacostia River—for two months, demanding early payment of bonuses promised them for their service. Most were owed $600 ($15,000 in 2025 dollars)—a considerable sum, and a lifeline, in the depths of the Great Depression.

But Hoover dismissed them, claiming that half were “not even veterans” and insisted that “communists” were behind the protest. Army Chief of Staff Douglas MacArthur, supported by Major George S. Patton and Major Dwight D. Eisenhower, ordered 1,000 soldiers—cavalry, tanks, machine-gunners and infantrymen— to subdue the “bad looking mob” whom he labeled “insurrectionists”. Unwilling to acknowledge the composition of the protesters, MacArthur insisted “if there was one man in ten in that group today which is a veteran, it would surprise me”.

The vast majority were indeed veterans, and like the four-million-strong Army at-large, one in five were immigrants including Lithuanian William Hushka of Chicago. Shot through the heart, he died instantly. Eric Carlson writhed in agony for four days before succumbing to his wounds. By then, the Xth Olympiad was underway in Los Angeles.

Los Angeles, the Great Migrant City

When Vice President Charles Curtis opened the 1932 Olympics in place of the embattled Hoover, he did so in a city of migrants and immigrants. No one, it seemed, was truly from Los Angeles. Of the 2.2 million people living in Los Angeles County at the time of the Games, just one in five were born in California. Most had migrated from Texas, Arkansas, Missouri, Oklahoma and other parts of the country, but all were branded “Okies”. Nearly 90% of the population was white.

Then, as now, Los Angeles also had a large (15%) immigrant population. But unlike today where Latinos predominate (49% of the current population), most immigrants living in the city of 1932 came from Italy, Germany and the rest of Europe. More than 50,000 Mexican nationals called LA home in 1930 (plus another 100,000 US citizens with Latino/Hispanic heritage), but as jobs disappeared during the Depression, many returned south of the border.

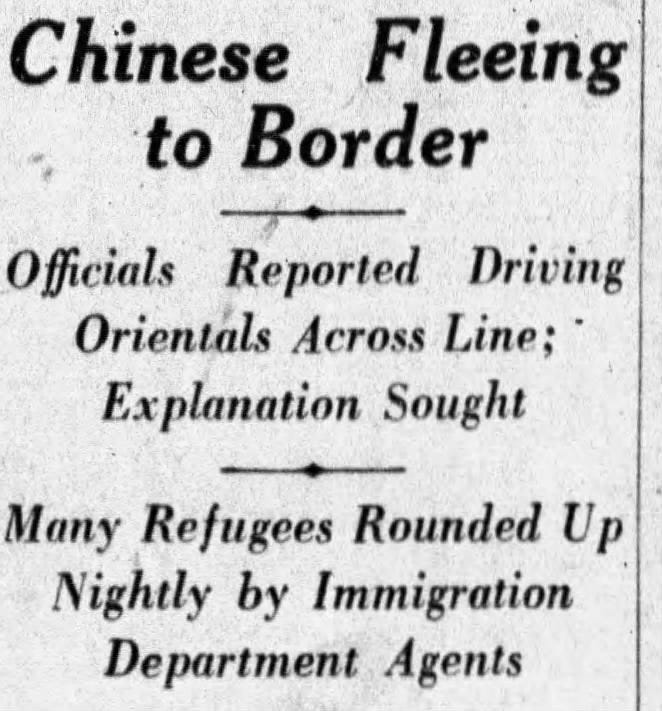

Reality didn’t stop those in power from laying blame with the “aliens”. On the eighth day of the Games, the Los Angeles Times reported that “thousands” of Chinese immigrants—barred since 1882 by the Chinese Exclusion Act—had been helped across the border by Mexican officials. Los Angeles’s Chief of Police told a reporter: “Most of our crime problems are caused by aliens without respect for the laws of the country.”

Legacies

Private First Class Eric Carlson was laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery a week after he’d been shot. None of his three brothers from California were able to attend the service, but Washington, DC Police Commissioner Pelham Glassford, himself a veteran, paid his respects.

Herbert Hoover lost the November 1932 Presidential Election in a true landslide. As Franklin D. Roosevelt reportedly told an aide after the ugly scenes in the nation’s capital, “there is no need now to campaign.”

The Bonus Army may have lost their battle in 1932, but they eventually won over Congress with passage of the 1936 Adjusted Compensation Payment Act. Their protests led to a rethinking of how we treat our veterans and, ultimately, to the GI Bill of 1944. More than 25 million Americans and their families have since benefited.

Ugly stuff.. There's a reason William Manchester entitled his biography of MacArthur, "American Caesar." People always think the Yalu in '50 was his "Rubicon", which he in the end did not cross, and accepted his dismissal as commander in Korea and returned to civilian life. But the Anacostia River in '32 was a better fit. He ignored Hoover's orders not to cross it, and instead used force against veterans-protestors. Hoover should have fired him on the spot, But Hoover showed his lack of spine, and allowed it to happen.

No parallels to today. ;)