Bowerman's Inspiration

Before Prefontaine, Nike or Hayward Field Magic, Oregon had Ralph Hill

Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, August 5, 1932: As the men’s 5000-meter race entered the final mile, no one was surprised to see two “Flying Finns” at the front. Even before Finland had freed itself from the Russian Empire, their runners had dominated Olympic distance-running.

But they had unexpected company with four laps to go. Ralph Hill, the nearly six-foot, 145-pound gangly Oregon farmer’s son tucked in on the rail. Wearing #433 on his USA tank top, he shadowed the smaller Finns in their blue crew-neck t-shirts. The former University of Oregon star wasn’t a complete unknown, having set an American mile record two years earlier, but he was hardly a favorite in this twelve-and-a-half-lap race. Five of the finalists came to Los Angeles with faster personal bests and Hill’s best—in his three previous attempts at the distance—was more than half-a-lap behind Lauri Lehtinen’s world record.

Los Angeles sports writer Maxwell Stiles hadn’t named Hill, now representing San Francisco’s Olympic Club, as one of the top ten competitors in the event three months before the games. Nor was Hill mentioned as a medal contender by USC coach and U.S. track official Dean Cromwell when he told an interviewer: “The United States has produced no good distance runners for many years, and in anything over a mile our men seem hopelessly outclassed… Our best may surprise by placing, but it hardly seems likely. When it comes to distance running the Finns have it all their own way.” Even the official Olympic program had Ralph listed as Bob Hill. Hill himself told a reporter after he appeared at ease in winning his semi-final heat three days earlier that Lehtinen “should win the 5000.”

A laughable false start spoke to the jitters of the 14-man field, but once they got away cleanly Hill shot to the front with a suicidal 63-second opening lap. Realizing his insanity, he moved towards the back as the field strung out single file through a still-torrid 2:47 opening kilometer. The pace was more than 20 seconds under the world-record clip, and although the weather gods blessed them with temperatures in the 70s, low humidity and no wind, contenders dropped one by one. By half-way only six challenged for the medals.

The men in front were all classic mid-foot-striking distance runners, but Hill, the collegiate middle-distance star, still ran up on his toes. The Finnish attaché had even admitted that Hill could be a “real test” for their athletes if only he adopted the more efficient “northland form” of their great distance runners.

From Henley to Hayward Field

Ralph Hill started running with his older brother Clarence on their family’s 200-acre Mt. Laki potato farm in Henley, fifteen miles north of the California state line and four miles southeast of Klamath Falls, dubbed Oregon’s “City of Sunshine”. Once a 4,000-foot-high desert landscape, the bustling railroad logging hub and farming community of 16,000 had been made possible by damming the Klamath River, draining marshlands, and creating hundreds of miles of new canals which irrigated more than 200,000 acres. Along these canals, in the shadow of 6,500’ Stukel Mountain to the east and with Mt. Shasta, the snow-capped 14,000’ volcano looming to the south, the Hill brothers ran.

Clarence was the more accomplished runner, but Ralph joined him on the University of Oregon’s track team—the “Webfoots” (they became the Ducks in 1947)—and showed promise as a freshman. Long-time coach Bill Hayward took note, awarding him the most improved trophy. By his sophomore year he had eclipsed his brother and battled some of the nation’s top milers. More was to come.

Hayward had coached several champion sprinters, but Hill was his first distance-running star. The cantankerous sixty-two-year-old coach, and Hill, the modest, quietly confident farm boy, were an odd couple. But their relationship worked because they shared a deep competitive streak. Hill built his endurance each summer with long runs around the farm, along the railroad track and up into the Great Basin Range. Although “altitude training” wouldn’t be widely appreciated until the 1968 Mexico City Games held at over 7,200’ forced coaches to consider the effects of lower oxygen levels, Hill may have been ahead of his time running above the generally-accepted beneficial training altitude of 5,000’. As he said himself, he liked the “clean mountain air” and felt like he had “super endurance” when he ran back down in the valley. Once back in Eugene, Hayward fed him a steady diet of spring interval training and the same high-knee drills Oregon’s sprinters practiced.

Two years after Hayward Field hosted its first football game in 1919 with bleachers from the old Kincaid Field, the university added a six-lane cinder track. It included a 220-yard straightway on the east end of the oval and, by 1928, a covered grandstand. What is now the most-hallowed (albeit completely rebuilt) track in America would enjoy its first bit of Hayward Magic just two years later.

An American Record

On Saturday May 17, 1930 Hill dug his toes into the cinders against the University of Washington’s Rufus Kiser, the 1928 NCAA mile champion. A small Hayward Field crowd, including Hill’s parents and a freshman football player named Bill Bowerman were on hand to watch.

Kiser blazed the opening quarter-mile in 59 seconds, but then slowed to laps of 65 and 66 seconds. Despite a lot of talk about the benefits of even pacing, most milers of the era started ridiculously fast because fields were often jammed with twenty-five runners or more, making it difficult to pass. But on this day, there were only four.

Hayward would later say that Hill’s “pace and endurance” work had paid off and that the “secret of running the mile is to distribute your speed and strength evenly throughout the race.” Hill wasn’t doing that, but whatever the pace, there he was on Kiser’s shoulder as they came into the homestretch. And unlike the year before, when a dog ran onto a sodden Seattle track, Hill didn’t falter in the closing yards. He ran through the finish line four strides to the good with a new American outdoor mile record.

His 4:12.4 was the fifth fastest mile ever run, two seconds off Paavo Nurmi’s world record. Bowerman, Hayward’s coaching successor and Nike co-founder, later credited Hill’s impressive run that afternoon with inspiring him to join the track team.

The Olympic Final: And Then There Were Two

The Finns continued to share front-running duties and with just two laps remaining Lehtinen surged again in the hope of breaking the spirit of the American challenger. But when he heard the crowd erupt, he knew that he had only managed to drop his compatriot, not Hill. They were 70 yards clear of the field.

The 80,000-strong Coliseum crowd rose to its feet, aware that they were witnessing a race for the ages. Never before had an American medaled in the 5000-meters, let alone challenged for the gold. His coach had once said that Hill had “one good race in him each year,” but this was something special. Hayward was there serving as an assistant US team coach for a sixth and final time. So too was Hill’s father and brother, and Joe Knudson from the First National Bank of Klamath Falls. Peering through his field glasses near the top of the grand stadium from row sixty-eight, he took pride knowing his fundraising efforts had supported the young man’s Olympic quest.

If Bowerman had been impressed watching Hill’s American Record in the mile, he was truly inspired watching the Olympic final that day. He later recounted that Hill’s performance planted the seeds that anyone, even a fellow Oregon farm boy, could run with the world’s best if their training and race tactics were well-executed. As he later told his home-grown Olympic stars Bill Dellinger and Steve Prefontaine, “Victory is in having done your best. If you've done your best, you've won.” Hill was doing his best. It remained to be seen if he would also break the tape first.

A Controversial Finish

Coming off the final turn, Hill ran just off Lehtinen’s right shoulder and swung wide into lane two—just as he had in setting his mile record. But as he did, the Finn drifted wide, blocking his path. Hill stutter stepped and moved back inside with fifty meters to go making a second attempt to pass. But Lehtinen looked to his right and, no longer seeing Hill there, surged back inside, slowly squeezing Hill’s direct path to the finish. His momentum gone, Hill could not respond. A few strides from the line, the Finn eased up, glancing repeatedly to his left. Hill made a final desperate bid for the win, but came up just six inches short. Both men were timed in a new Olympic record 14:30.

The first boos of these otherwise Golden Games rang out from the partisan Coliseum crowd almost immediately. Although the Japanese trackside official thought a foul had been committed, chief track judge Arthur Holtz of Germany ruled that Lehtinen had not “willfully interfered” with Hill. After an hour’s delay, much of it punctuated by jeering fans, the decision was met with a “Bronx cheer”. Public address announcer Bill Henry pleaded over the stadium’s twenty-three loudspeakers, “Remember, please, these people are our guests!”

Hill refused to file a protest, but American newsmen were less forgiving. The Los Angeles Times’s Braven Dyer wrote that the Finn may not have technically committed a foul, but he had “violated the spirit of amateur competition.” Stuart Cameron gave Lehtinen the “unofficial award for most un-sportsman-like act of the games.” Nineteen-year-old future U.S. President Richard Nixon had come to the Coliseum that day from Whittier—one wonders what he might have said about the whole cheating accusation.

Where Lehtinen was cast as the villain, "as popular as the proverbial young lover with halitosis”, Hill quickly became the “Hero of the Games.” Jean Bosquet called Hill “gallant” while the New York Herald Tribune’s George Daley wrote that Hill “earned more renown in defeat than he would have gained glory in victory.” More than fifty years later, acclaimed Olympic documentarian Bud Greenspan reflected on the race: “Today, Ralph Hill would have protested… the gold medal would have meant commercials.” Hill, ever the stoic figure, would have none of it. When asked what he would do at the end of the Games, he responded matter-of-factly, “I guess I’ll go back to the farm.”

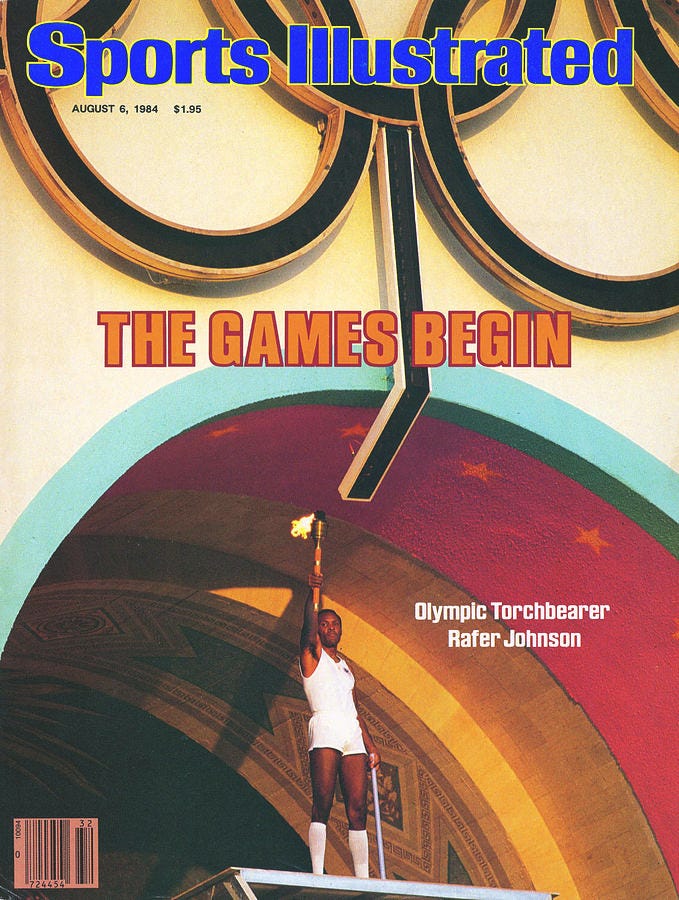

The 1984 Olympic Torch Relay

On May 8, 1984 the Olympic Torch Relay began a more than 9,000-mile journey from New York City to Los Angeles. Along the way, 3,636 torchbearers across 33 states were entrusted to carry the flame including a 76-year-old polio survivor from Klamath Falls, Oregon named Ralph Hill.

As we approach the 50th Prefontaine Classic this July 5th, it’s important to remember those who came before. The Three Bills—Hayward, Bowerman and Dellinger—Pre, Rupp, Centro, and the first Oregon distance-running star, Ralph Hill.

I wish the '28 LA Games were happening this summer! Your book will make everyone feel the same way!

Well done as always Josh!