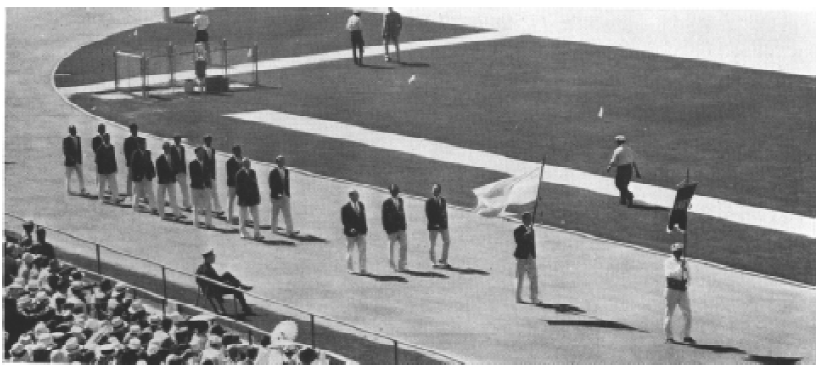

1932 Olympics Opening Ceremony

"If you don’t have goose bumps, there’s something wrong with your constitution."

Charles Harwood had seen a lot in his 101 years. Born in Vermont in 1830, he graduated from Williams College in Massachusetts, founded Missouri’s Drury University, championed the development of California’s citrus industry, and served as a trustee of Pomona College. Upland’s “grand old man” had lived a true centenarian’s life. But he had never witnessed anything like the scene unfolding before him in the Coliseum on July 30, 1932. No one had.

The Parade of Nations

The Greek sprinter, momentarily blinded by the mid-afternoon sun, entered to a mighty roar through the west end portal. The capacity crowd had been filling the stadium for three hours and now their excitement reached a fever pitch. Christos Mantikas would compete in four events in Los Angeles, but no mere race would compare to the moment at hand.

Given the honor of carrying the sky blue and white cross Greek flag, the twenty-five-year-old from the Aegean island of Chios led a contingent of ten track athletes, boxers, and wrestlers—all sports befitting the home of the ancient Olympics. And by a tradition started in the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics and continued to this day, Greece, as ancestral home of those ancient games held the cherished role of leading the procession. The opening ceremonies had begun.

Described by one teammate as “a handsome guy” who “attracted all the women,” Mantikas strode with a certain dignity in his blue blazer and white trousers. His right hand steadied the flag and as he marched down the track, the crowd enveloped him. Behind him, 2,000 athletes, coaches, and officials from 37 nations assembled on Menlo Avenue awaiting their own goose bump-inducing moment.

An hour earlier the men had boarded dozens of buses in the first purpose-built athletes’ Olympic Village atop Baldwin Hills before following a ten-minute police escort to the stadium. The 127 female athletes competing in track & field, swimming & diving, and fencing arrived separately from their quarters at the Chapman Park Hotel on Wilshire Boulevard. As one film commentator opined, “One of the most impressive sights you’ll ever see in any sporting event ladies and gentlemen.”

It truly was an impressive sight. The 800 journalists, including 200 from abroad, packed into the press box agreed. Surveyed by the Associated Press earlier in the year, sports writers wanted to cover the Olympics more than any other event—ahead of the World Series and Kentucky Derby. And despite nearly half of all American households owning a radio, organizers prohibited live broadcasts for fear of cannibalizing ticket sales. This was one of those special you-had-to-be-there events.

A thousand feet overhead the 128-foot-long, twin-engine Goodyear blimp Volunteer captured film and photographs of the awesome scene alongside an auto-gyro (a precursor to the helicopter). Despite the depravations of the Great Depression, Angelenos had paid $3 each ($70 in 2024 dollars), or nearly a quarter of a million dollars in total ($6m in 2024 dollars), to experience the spectacle—and 50,000 more loitered outside unable to gain entry. Above the eastern peristyle entrance those beyond the gates would have seen a 17-foot Citius, Altius, Fortius medallion above hedges shaped in the form of Olympic rings.

Aggressive souvenir vendors, program salesmen and newsboys pestered spectators with their offers. Most of the men were finely clothed in light dress suits, ties, and ubiquitous straw boater hats. The ladies did their best to stay cool under cloche hats and colorful parasols. Blue and white capped ushers—anyone with connections to Olympic officials got the coveted posts—filled the stairs. Sixty plain-clothes detectives watched for pickpockets. Never had so many people attended an Olympic event. Four years earlier, only 28,000 marked the opening ceremony in Amsterdam.

His pulse surely racing and his eyes adjusting to the sunlight, the young man at the head of the parade heard music from the 300-piece Olympic band behind him from a lower section of the west end stands. They would play his and each of the participating nations’ marches over the next thirty minutes before finishing with John Philip Sousa’s Stars and Stripes Forever when the host nation entered the stadium. The twelve-hundred-voice choir, dressed all in white save for the colors of the Olympic rings emblazoned on their caps and on sashes around their waists, had just finished singing The Star-Spangled Banner. Although recognizable to all Americans, it had only become the nation’s official anthem a year earlier.

In front of him to the east he saw the stadium’s great peristyle and flags of the competing nations fluttering above the arches in the gentle breeze. Higher still, atop the distinctive central arch, 27-inch-tall letters large enough to read from all 79 rows of seats unfolded on the scoreboard:

“The important thing in the Olympic Games is not winning but taking part—the essential thing is not conquering but fighting well.”

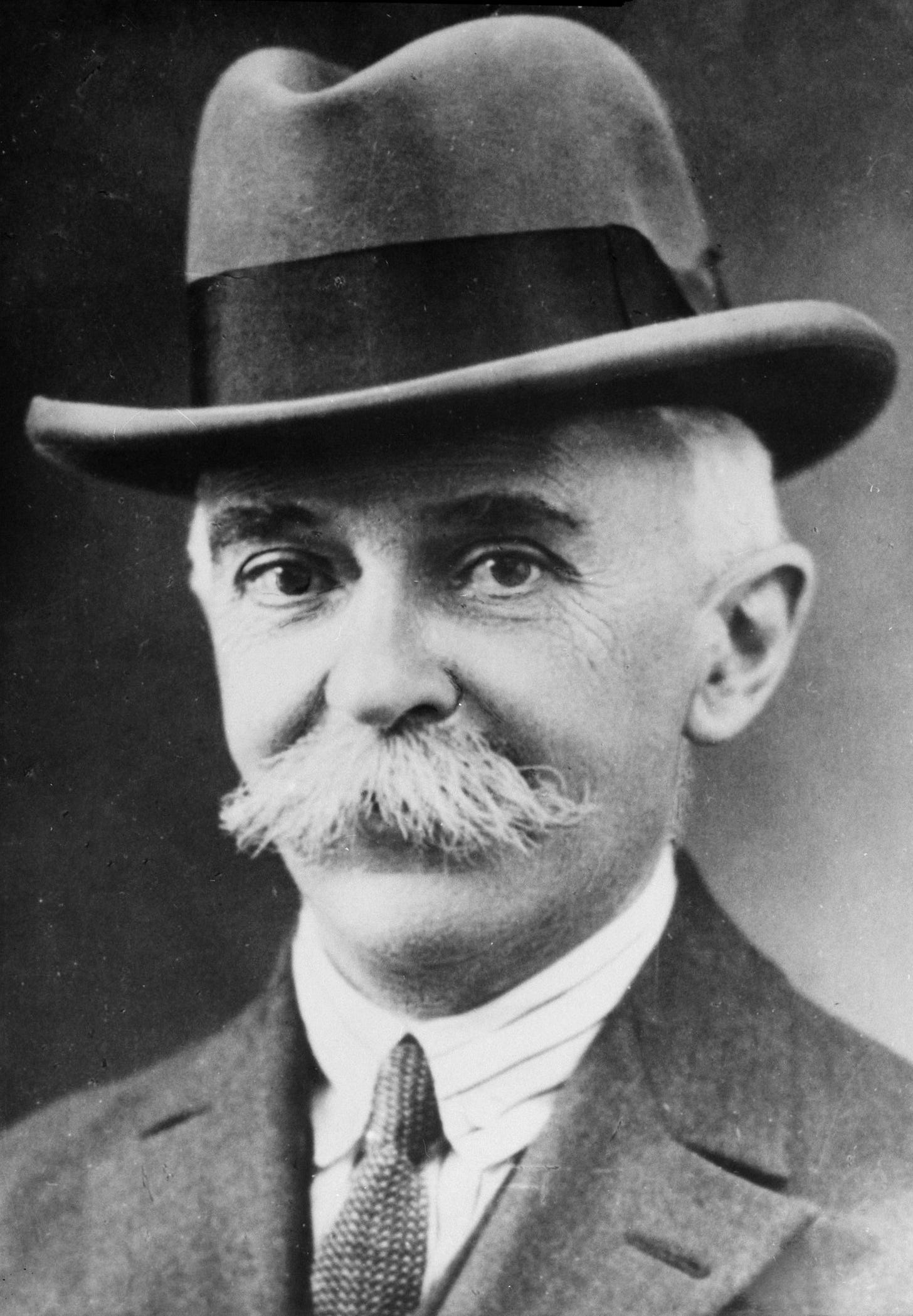

The Little Baron

Baron Pierre de Coubertin, father of the modern Olympics and founder of the International Olympic Committee (the “IOC”), was not present in Los Angeles but his presence could not be missed. Though inspired from a sermon he heard during the 1908 London Olympics in Saint Paul’s Cathedral by Ethelbert Talbot, a Dartmouth College graduate and an Episcopal Bishop of Pennsylvania, these words came to be associated with Coubertin as the Olympic creed.

Not on the scoreboard but printed in the thousands of ten-cent souvenir programs scattered throughout the stands was the Tenth Olympiad logo featuring the Olympic motto, first proposed by Coubertin in 1894 and officially adopted by the IOC in 1924: Citius, Altius, Fortius—Latin for Faster, Higher, Stronger. Coubertin believed these words represented “moral beauty” and that the Olympics “role and destiny is to unite the past and the future through the fleeting moments of the present. They are the ultimate celebration of youth, beauty, and strength.”

Mantikas led the world’s best athletes—Coubertin’s youth, beauty and strength personified—down the track, pausing momentarily to acknowledge the Tribune of Honor to his right in the south end stands. Most of the 800 Olympic officials, politicians, military brass, and other dignitaries sported black top hats (“toppers”) and formal dress suits despite the 80-degree California sun.

A Hollywood Production

By the late-1920s, with the end of the silent movie era, filmmaking had become LA’s leading industry. More than 35,000 found employment in the eight largest studios and ancillary businesses. But then, as now, the stars made the city famous. And they came out in force when the Olympics came to town. Douglas Fairbanks, Clark Gable, Tallulah Bankhead, Joan Crawford, Norma Shearer, John Barrymore, the Marx Brothers, Gary Cooper, Bing Crosby, and Cary Grant were all on hand. But on this occasion, the athletes played the starring role, and the film stars were the adoring fans.

After the official opening of the Xth Olympiad, the now-familiar pageantry, speeches and oaths of opening ceremony protocol followed. Six trumpeters blared their horns as one from the ramparts atop the peristyle. A ten-cannon salute—ten blasts to mark the tenth Olympiad—pierced the air from outside the main gates. And at last, the torch was lit in the newly-added Coliseum cauldron moments before the raising of the Olympic flag and the release of hundreds of homing pigeons (filling in for the traditional peace doves).

When 1932 US water polo goalie Herbie Wildman reflected back on his experience at the opening ceremony some 52 years later his passion overflowed:

“There’s nothing like it. You can’t imagine the exultation or the thrill. It’s hard to explain. It’s kind of like an earthquake—until you’ve been through one you just can’t imagine the feeling. It’s unbelievable… When they play the ‘Star-Spangled Banner’ and they open the games and light the torch, tears run down your cheek, and the chills go up and down your spine. I’ll tell you, if you don’t have goose bumps, there’s something wrong with your constitution.”

Not until the 2000 Sydney Olympics opening ceremony would a larger in-person crowd witness an Olympic event. No Adolf, not even in Berlin in 1936.